The "Waverley" Phenomenon and Material Imagination

12th November 2020

We were delighted that Lillian could join us for this important milestone in the Club's 126-year history, and especially pleased that she was able to provide us with such an accessible, nuanced look into her research into Scott's celebrity and its reverberations in the material imagination in the nineteenth century.

Lillian is a third year postgraduate research student in the School of History of Art at the University of Edinburgh. She is funded by the Chicago Scots R. Harper Brown Scholarship as well as the Ruth Elizabeth Southworth Scholarship supported by the Kappa Alpha Theta Foundation. Her thesis seeks to address the extent to which the literary celebrity of Walter Scott found currency in nineteenth-century visual and material culture in Britain. Examining sectors of popular print, portraiture, topographical media, material artefacts, historical dress and reenactment, her research evaluates prevailing conceptions of the author’s literary authority. How Walter Scott and the Waverley Novels informed the political, social, and intellectual fabric of their day is also continually brought into question.

Lillian holds an MA in Modern Art History, Theory & Criticism from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a BA in Art History and European Studies from DePauw University. Prior to commencing her doctoral study, she worked in Museum Education and the Department of Prints and Drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago. She currently holds a position as an online instructor of art history for the University Texas at El Paso and Youngstown University.

The Waverley Phenomenon and Material Imagination

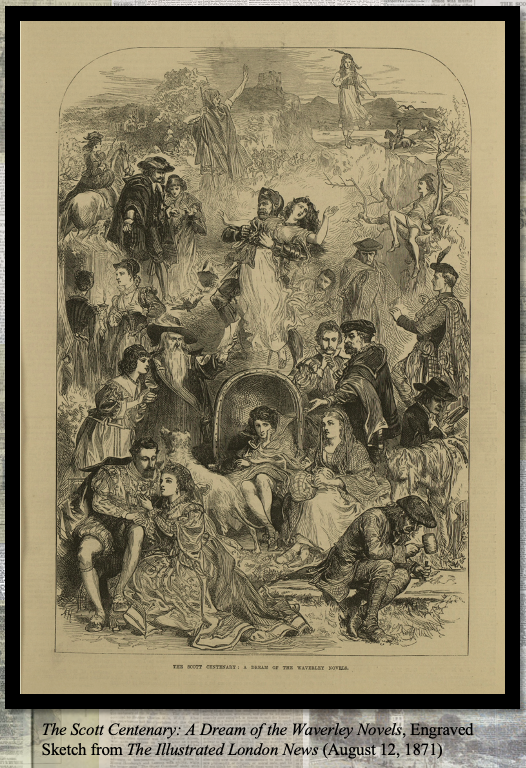

I’d like to begin my lecture this evening with the following item found in the Bridgeman Art Library in London: an engraved sketch which appeared in the 1,664 issue of The Illustrated London News on Saturday, Twelfth of August 1871. Entitled A Dream of the Waverley Novels, this image was one of roughly 30 full-page illustrations produced for The Illustrated London News in the summer months of 1871 which sought to pictorialize the legacy of famed author Sir Walter Scott on the 100th anniversary of his birth. The Scott Centenary was a landmark occasion observed across numerous towns and cities in Britain and North America. Aside from the Annual International Exhibition of Arts and Industries, this event received more coverage in the English-speaking periodical press of 1871 than the wedding of Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll and the Paris Commune combined.

Parades, festivals, art exhibitions, costume balls, theatre, and local assemblies honoring the beloved poet and Author of Waverley were far flung and wide-reaching. This commemorative strain reached a highpoint in the National Festival in Celebration of the Centenary of the Birth of Sir Walter Scott which took place in the city centre of Edinburgh, Scotland over 3 weeks and attracted some 12,000 participants. When we take into consideration the fact that, by 1871, Scott had already been dead for nearly 50 years, the of currency of his celebrity in the culture climate of the English-speaking world at this moment in time is striking. It begs the question: what exactly did Scott mean to the nineteenth century? Picking up where contemporary modes of assessment left off, this, I would argue, is where the work of the art historian comes into play. Examining sectors of popular print, portraiture, material artefacts, visual entertainment, and public media we can evaluate the then prevailing conceptions of the author’s literary authority in a manner that both compliments and builds on the tradition of literary criticism, the dominant standard of study in the field of Scott scholarship for over a century.

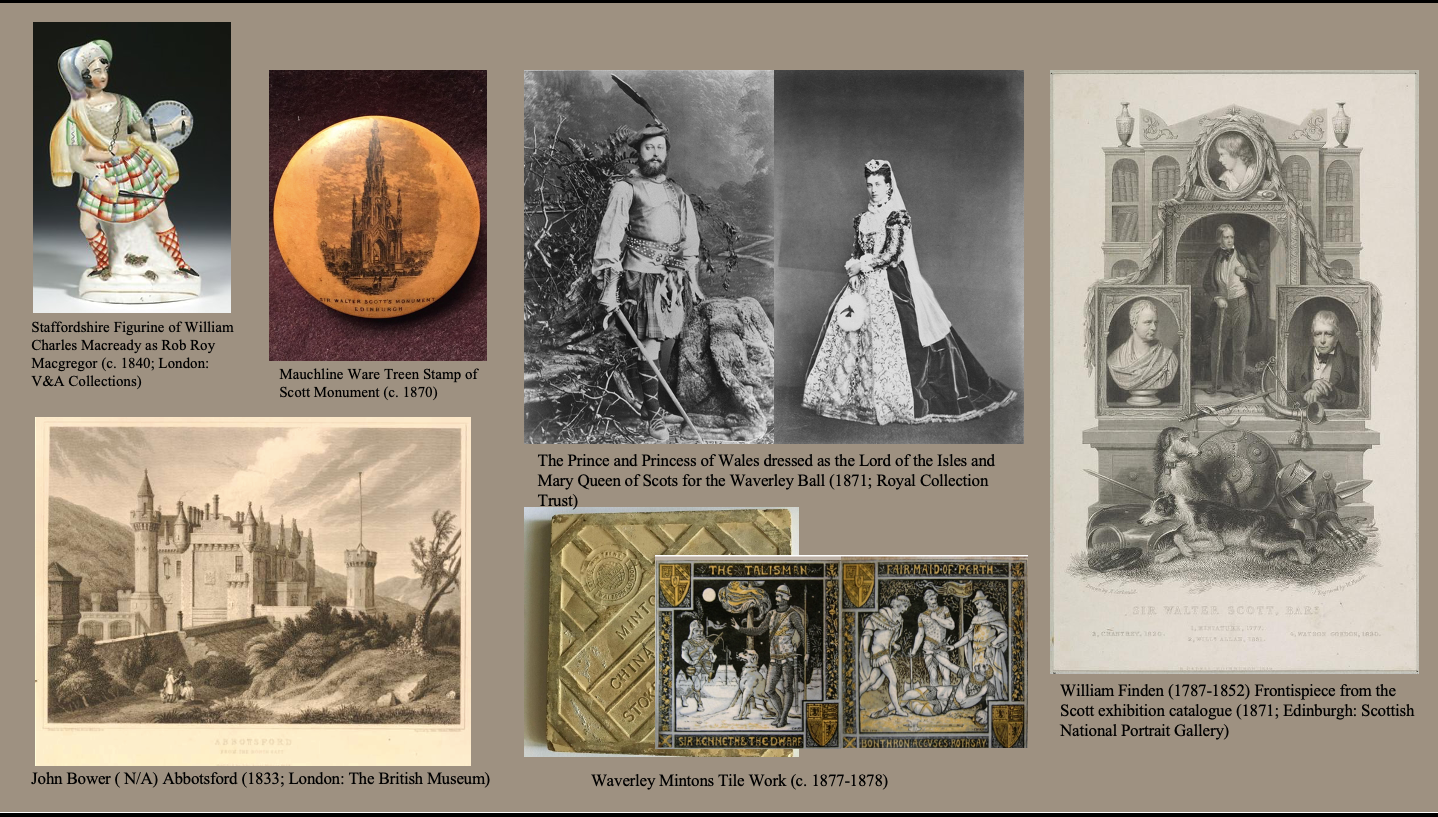

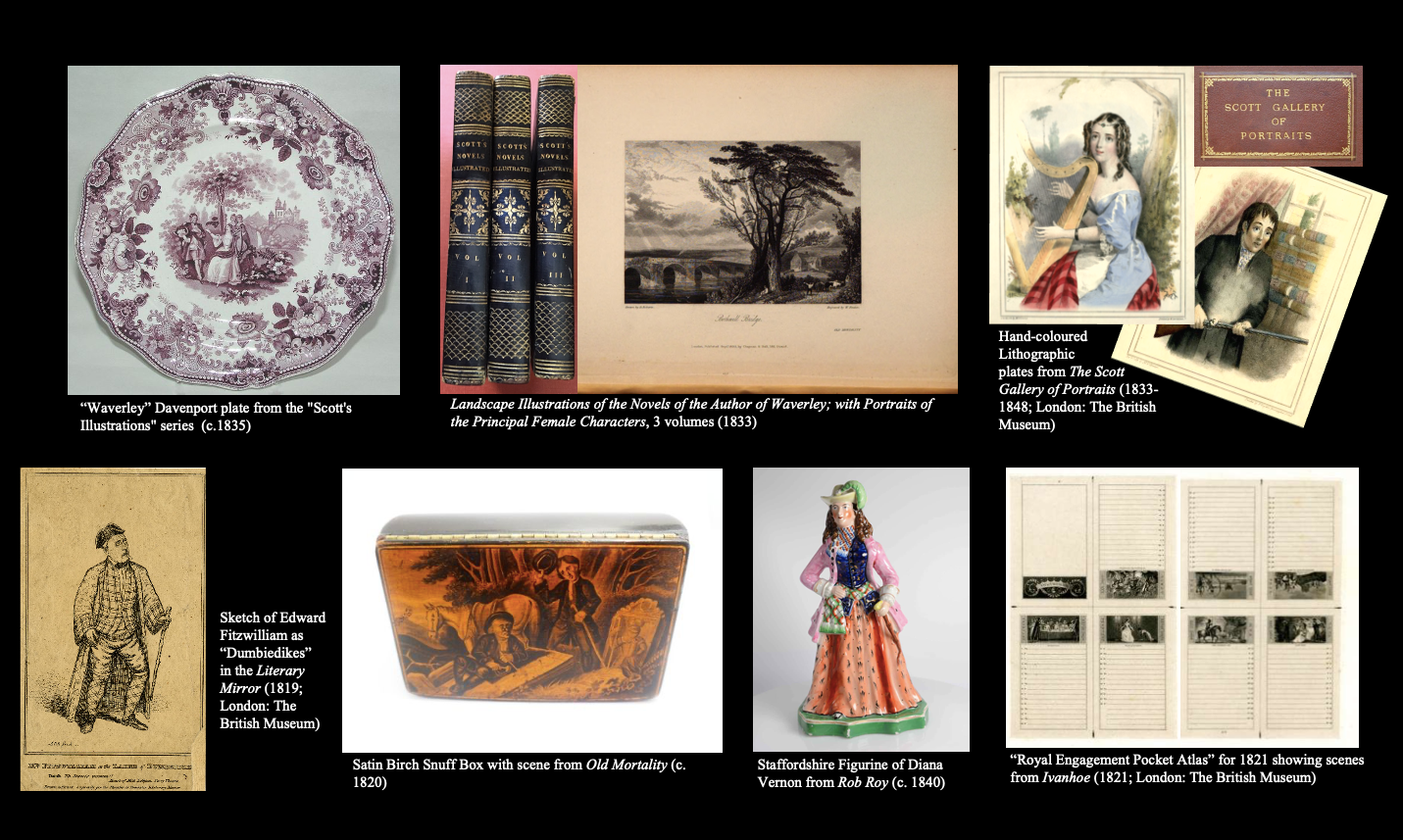

Interestingly enough, art history rarely enters into conversations regarding the reception history of Scott and the Waverley Novels. This might seem understandable. Why study the image and influence of one of Britain’s most prolific writers any other way than through the texts upon he attained national, indeed, international status? Its only when confronted with curious images and illustrations, even artifacts, such as the ones shown here that a case for the visual and material afterlife of the author becomes evident. I use this term in reference to the work of Scott scholars Anne Rigney and Nicola J. Watson, two of only a handful of individuals within the sphere of literary studies today who have drawn attention to the manner in which both Scott and his literary corpus were subject to and inspired countless modes of artistic production and consumerism in the nineteenth-century in Britain; here the literary life and practice of the author took on a new and ever-expanding corpora of identity. In addition to showing the fluidity of stances with which nineteenth-century readers made sense of and came into contact with the figure of Walter Scott, what we can infer from the gleanings of this rich media ecology are the various strands which comprised and fed in to Scott’s cultural phenomenon. Disentangling, and, at the same time, engaging with just a few of these fields of activity, I hope to show you this evening, how in conjunction with the study of texts, we can use art history as a tool to calibrate what shaped the literary celebrity of Scott in the nineteenth-century and made him a formidable presence and point of reference in visual and material culture.

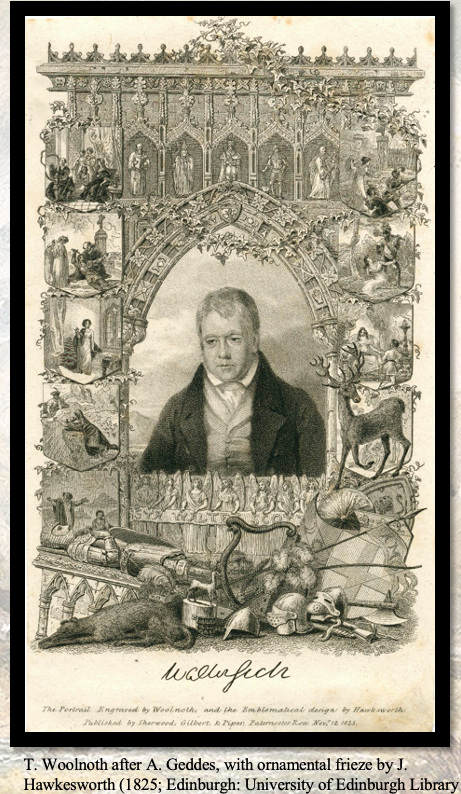

One, and arguably the most distinctive, feature of Scott explored in nineteenth-century valuation was the repertoire of historical images and character portraits established in the Waverley canon. Scott, as I suspect most of us know already, was an effusive storyteller. His belief in the creative continuity between life, literature, and art began with a career in poetry and ballad writing, where, paying special attention to descriptive imagery in his work, the author won the favor of the reading public in Britain for his energetic and highly-colored representations of historical life and subject-matter. The impetus of his early writing, Scott once explained in a historical note from 1819, was the “conjuring of images through words.” Reminiscing on the process by which by which his literary productions came to fruition, the author explained how “weary with ransacking [my own] barren and bounded imagination [ . . . ] I [ . . .] looked out for some general subject in the huge and boundless field of history [ . . .] bedizened it with coloring [ . . .] ornamented it [ . . .] and invested it with such shade of character as would best [ . . .] present [ . . .] to the reading public a lively and fictitious picture.” In time, this poetic tradition transitioned into a novelistic enterprise. From the din of bagpipes, the history of castle architecture, great halls, wood-beamed taverns and rocky glens, to costumes, countenance, art, objects, furniture, even hair style, a finely-drawn world of historical individuals, stories, and spheres loomed large in the Waverley Novels and catapulted Scott’s distinction in the literary firmament as a pictorial writer. One can venture to guess that this is the prevailing viewpoint taken in T. Wolnoth and J. Hawkesworth’s engraving of the author from 1826. In this work, a lavish gothic border with ivy and escutcheons depicting scenes from the poetry of Scott ornament his half-portrait. It extrapolates from the claim made by literary critic and Whig reformist, Lord Francis Jeffrey, that the Minstrel of the North was the most brilliant literary portraitist of his age, one who’s “animated [and] engaging exposition [. . .] of the manners and state of past society” presented to readers the same “truth and vivacity of coloring” as paint to canvas.

This pictorialism, compounded by the sheer exhaustiveness of Scott’s literary imagination, gave rise to more concrete visions of historical spheres and subject-matter in Britain. Scott wrote a staggering 27 novels in 18 years – not mention 9 metrical romances, 5 editions of collected balladry, and over a 50 book projects in history and prose fiction. With topics ranging chronologically from ancient Byzantium all the way to modern European history his literary outpouring offered artists and craftsmen a wealth of original material. The engraving A Dream of the Waverley Novels illustrates the pictorial repertory associated with this body of works. Here we see historical characters, period clothing, and landscape – each taken from a unique chapter in the literary corpus of Scott – coalesce in the space of a single page. Looking at the composition, the expression “Great Scott” certainly comes to mind, but what I find intriguing about this print is the letterpress which accompanies it. The writer posits that “having read the admirable stories [ . . .] to the many volumes of Scott’s novels [ . . .] the viewer will have no difficulty in identifying all the characters or figures represented.” He continues, “we shall leave the reader to their unassisted contemplation [ . . .] for all that concerns the subjects and incidents [ . . .] associated with the Author of Waverley are long to be remembered and [therefore] recognizable even at a glance.”

Recognizable even at glace: this is, of course, merely one take on Scott. But it elucidates the component to his literary celebrity which nineteenth-century readers and reviewers of Scott and the Waverley Novels enthused over and expatiated on in their critical valuation of the author, many times over. According to historian Thomas Carlyle the “singular vividness” with which Scott wrote about the historical past ranked him among the chief wonders of the western world. His force and clarity of description, Carlyle argued, dazzled readers where previous modes of historiographical expression and novel-writing in the English literary tradition failed. In his Memorials of 1856 Lord Henry Cockburn similarly described the appeal of Scott as a “graphic force and universal sensation.” Extolling his ability to bring history out of obscurity and into popular consciousness through writing English essayist and literary critic William Hazlitt labelled the author the Amanuensis of History. In a retrospective essay on the Author of Waverley published in 1825 he asserted: “this author has only to describe [ . . .] and everywhere [his material] speak[s], breathe[s], and lives[s] again [ . . .] Whatever [. . .] he transfers to the pages of his fiction we [ . . .] see, hear, and feel [ . . .] with untired interest.” It’s worth noting that while Carlyle, Cockburn, and Hazlitt were referencing the extraordinary impact that Scott’s writing had on the nineteenth-century reading public, implicit to its mass cultural response were the varieties of artistic adaptation, image-making, and media consumption derived from it. This is exactly what is shown in the image before you. Taken from the same issue of the Illustrated London News on the Twelfth of August 1871, this illustration showcases an exhibition of portraits and material artefacts associated with Scott and the Waverley Novels, which featured as a point attraction in the National Festival in Celebration of the Centenary of the Birth of Sir Walter Scott at the Royal Academy in Edinburgh.

Evidence for the vigor and vitality Scott bestowed to the subjects and subject-matter of his fiction can be seen in other illustrative works from the Scott Centenary too. This is one of my personal favorites, an oil painting by Victorian genre artist Charles Hunt. Entitled Ivanhoe, the image, like the previous engravings shown, signals Scott’s capacity to bring history and its visual and material aspects into view. Ivanhoe, one of the most critically acclaimed of the Waverley Novels in Scott’s day, is shown here as a children’s game, thus reviving the contention of one nineteenth-century literary critic for the Christian Observer who, in 1832, asserted that “the images and recollections [drawn up] in the Waverley Novels are now indispensable pieces of furniture [ . . .] in every corner of every home in the British empire.” Hunt would certainly seem to underscore this point in his use of child actors. Common to the painterly depiction of Victorian middle-class life, the ease with which these rosy-cheeked figures play out a scene from one of the Waverley Novels clues us into the nineteenth-century familiarity with Scott. Importantly, Hunt associates Ivanhoe with a domestic interior, thus showcasing the extent to which the book and many of the Waverley Novels saturated public and private consciousness as well as the visual and material complexion of things in everyday life. At centre we see two boys re-enact the famed tournament scene from the novel. Ivanhoe, a youth dressed in old infantry uniform and feathered helmet, sits staunchly astride a makeshift steed, while his adversary, Brian de Bois-Guilbert, a sweet-faced boy with unkempt hair and painted moustache topples backward off an upturned chair.

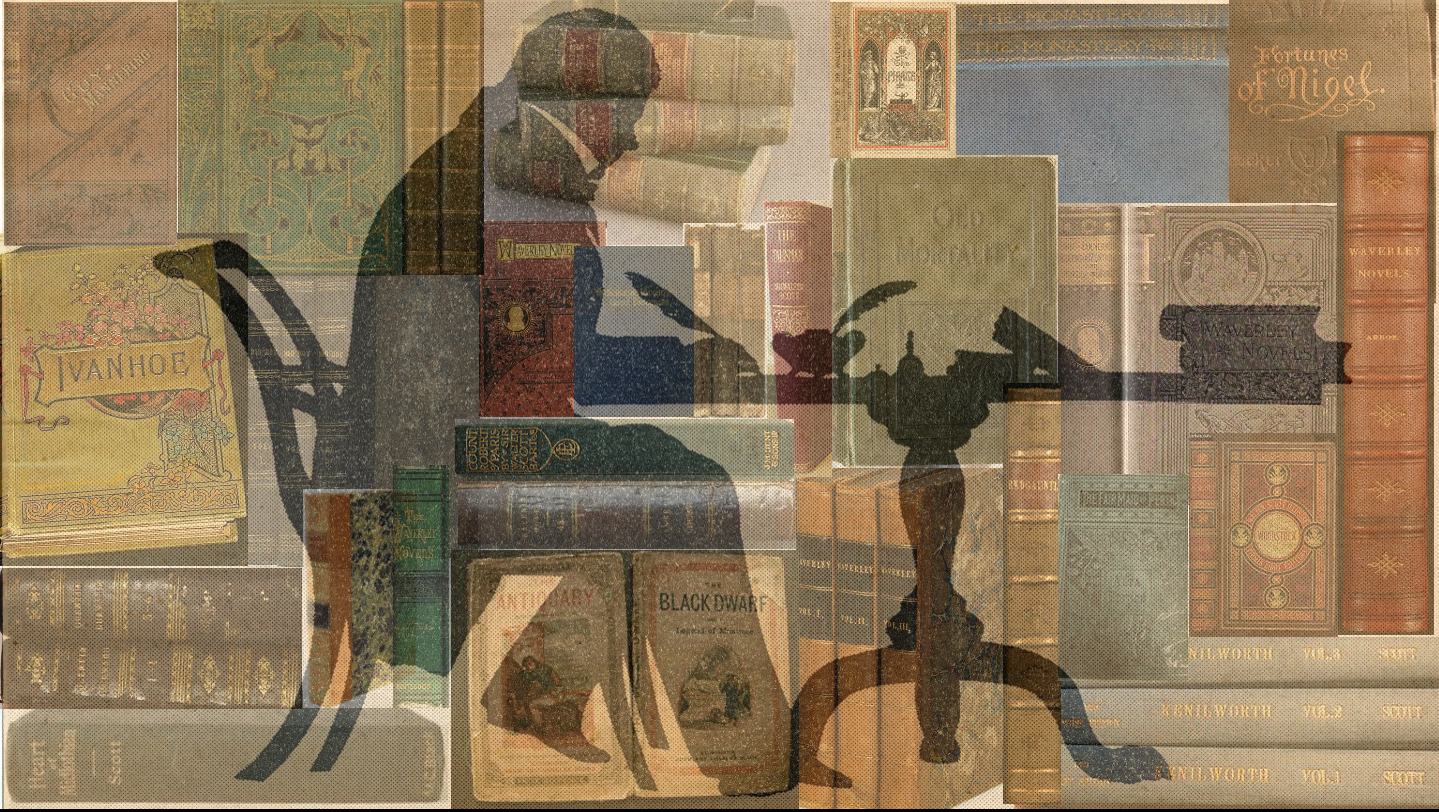

Moving beyond the literary associations depicted in this particular figural arrangement, we might also consider the significance of the discarded book pictured in the lower foreground of the painting Ivanhoe and the two reading boys, located at right. In possession of what we can assume are two small, feasibly abridged, juvenile, or perhaps even castoff adult versions of the novel Ivanhoe, these figures reference the currency of Scott within the mass-cultural circuit of print in the nineteenth-century in Britain. As Richard J. Hill has shown, the repertoire of historical images and character portraits established in the Waverley canon was eagerly taken up within the commercial movements of this industry. As early as the late 1810s and early 1820s the poetry and novels of Scott began to appear in collected, tranched-down, and illustrated editions. This placed Scott in the hands of an ever-widening literary audience, middling to monarchical.

Moreover, as a consequence of increased specialization in print technology and the book trade in the early nineteenth-century, the Waverley Novels made their way into chapbooks, picture books, keepsakes, illustrated subscription series, stand-alone works, and supplementary print. From this substantial body of secondary texts and images, then, arose an equally substantial outpouring of visual and material adaptations. What began as a distinctly literary phenomenon thus extended itself into the framework of Victorian life, leisure and domestic performativity. The items shown here represent just a few of the many products and commercial spin-offs derived from the Waverley canon, some of which likely made their way into the type of middle class household or domestic interior Charles’ Hunts children belong to in the painting Ivanhoe.

This leads into another point of discussion, separate but related to the pictorialism of Scott’s writing. Further to the nineteenth-century valuation of Scott was a keen public interest in getting to know the visual and material foundations upon which Waverley Novels were authored. Who was the man behind such “rich and varied [. . .] graphical productions,” questioned London Magazine in a review of the Pirate in 1822. To what “external imagery or machinery” did their author-creator turn to place his “effective compilation of material” so vividly before the eyes? We might recall that, prior to 1827, all of the fictional works of Scott, aside from his metrical romances, were simply known as the fictional works of the Author of Waverley. The question of Scott’s authorship, and, by extension, the origins of the Waverley Novels, thus played a role in cementing his celebrity. To the reading public, the Author of Waverley wasn’t just a literary worthy. He was the Great Unknown, a kind of romantic virtuoso and creative well-spring hidden from the world at large, but tantalizingly, ever-increasingly on the verge of public discovery. The images and newspaper clippings shown here represent the currency of this thread across nineteenth-century discourse. In particular, the satirical print located at center pokes fun at the rampant interest in the figure of the Great Unknown. In this print, a caricatured version of the Author of Waverley does battle over the biographical rights of Napoleon Bonaparte with the Duke of Wellington, the victorious commander of the British-led Allied army at Waterloo. His juxtaposition with two of the most famed and inquired after personalities of the day in Britain here thus conveys his status as a cultural mainstay. Further to the right, in a frontispiece engraving for the 1825 publication Illustrations of the Author of Waverley: Being Notices and Anecdotes of Character, Scenes, and Incidents Described in His Work we see a similarly comic but incisive take on the anonymity of the author. Located beneath the half portrait of a partially concealed figure of the Great Unknown a Latin inscription by Tacitus reads “that which is unseen, shines the brighter.” Aware of the promotional value of anonymity, Scott played in to the public interest in his figure, where, using a stratagem of carefully constructed displays of material self-fashioning and public performance, he advertised his link to the Waverley Novels and, at the same, obfuscated it in myriad ways. This excited the curiosity and interest of nineteenth-century readers in Britain and, in time, became a prominent point of focus in the media ecology which pictorialized his legacy.

With questions surrounding the character and occupational history of the Author Waverley frequently making an appearance in the popular print of the early nineteenth-century in Britain as well the literary and cultural constituencies to which it catered, Abbotsford, the home of Scott from the year 1811 until his death in 1832, became especially important to the nineteenth-century treatment of his literary life and practice. It was here that many intimates, collogues, and admirers of the author first bore witness to the secret of his identity. For those less familiar with the private life of Scott, it provided a point of speculation. The success of his poetry and the Waverley Novels enabled Scott to pour vast amounts of income into the creation and expansion of Abbotsford house. Over a period of thirteen years, the home transformed from a modest Border farmhouse into an extravagant Scottish baronial manor. Scott frequently referred to the Abbotsford estate and its holdings as the “Delilah” of his imagination, his “flibbertigibbet” and “romance of a house,” “Patmos,” “paradise,” and “least of all possible dwellings.” That built the environment of the home was envisioned by its author-inhabitant as a kind of monument to his creative outpouring was the signaled by the range artefacts, ornaments, and images cluttering Abbotsford. With references to history and romance scattered almost universally across the building and furnishings of the home, the sharpened sense of literary association there generated the assumption that it was here that the Great Unknown, the Author of Waverley, lived and worked.

To visit Abbotsford, therefore, was to gain access to the world Scott recreated through literature. The home became a popular tourist destination in Britain and a literary landmark well before Scott admitted authorship of the Waverley Novels in 1827. People found their way via coach and paddle steamer, but increasingly, through the mediation of books, illustration, and travel literature they visited Abbotsford virtually, through variant forms of printed media. This is what is shown in the collection of early nineteenth-century travel publications pictured at left, and, to the right, a series of stereoscopic images made and marketed by Scottish photographer George Washington Wilson. Moving left to right, we see photographic images of the Abbotsford entrance hall, the study of Scott, the Abbotsford Library, and the Armory.

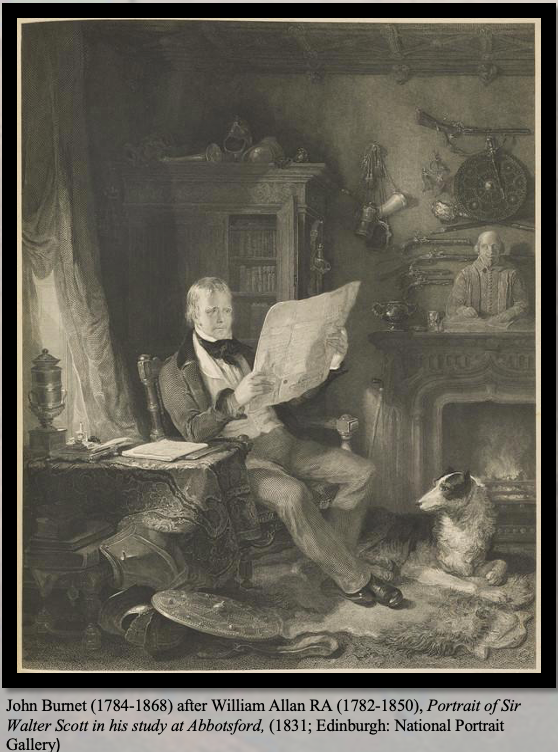

In another printed piece from 1832, line-engraver John Burnet copied and redistributed William Allan’s hugely successful oil painting for the Royal Academy exhibition of 1831: Portrait of Sir Walter Scott in his study at Abbotsford (1831). In this image, decorative, architectural, and antiquarian elements from across the built environment of Abbotsford are rearranged to create the impression of a working environment saturated in the sensory texture of times past. Scott, we see, sits contentedly engrossed with a weathered manuscript by Mary Queen of Scots in hand. He is surrounded by layers of drapery, carpet, animal fur, books, parchment paper, metal goods, and antique weaponry. How this surfeit of visual and material resources will factor into and enhance the historical fabric of the Waverley Novels is thus proffered for enquiry. This same invitation to engage with Abbotsford’s many points of literary and historical association is offered in the title page engraving of the Abbotsford Edition of the Waverley Novels. Looking at the print, a trove of curiosities belonging to Scott and his collection at Abbotsford lies scattered before the mouth of a gothic entryway. Tartan garments, weaponry, and other antique assortments suffuse the scene in a picturesque manner, allowing the eyes and imagination to wander from one object to the next. To the left, Scott’s deerhound Maida and a gaggle of smaller pups devotedly, if somewhat distractedly keep watch over the museal assemblage. Their inclusion in the scene alerts the viewer to the layer of domestic association implicated in the Waverley canon. Scott, it is rhetoricised here, is at home with the relics and remains of history both literally and figuratively speaking. As preface to his text, Abbotsford registers in this engraving as the site of his self-made genius, the very place where history (and the stuff of the Waverley Novels) are breathed, as it were, into life.

In time, the signification of Abbotsford became synonymous with the national historical inflection of Scott and the Waverley Novels too. This became key to the author’s reception in the 1820s onward as his literary life and practice were gradually and, at length, more intricately bound to the industry of Scottish cultural heritage. Early in his literary career Scott popularized the regional landscape and historical settings of Scotland with his narrative poems such as Lay of the Last Minstrel (1805), Marmion (1808), and Lady of the Lake (1810). With other early written works such as Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border and The Provincial Antiquities and Picturesque Scenery of Scotland he revitalized Scottish antiquarianism as well as the fading oral traditions of Scottish folklore and balladry. The graphic style of writing which typified the literary output of Scott not only glamorized real-life localities and communities across Scotland, but also charged them with enough human drama and visual appeal as to contribute to a major growth in the practice of Scottish landscape art, fashion, and literary tourism. Moreover, following his recovery of the Scottish Regalia and high profile role in the visit of George IV to Scotland in 1822, these activities all but confirmed popular suspicion in Britain that Scott was in fact the Author of Waverley. His physical and cerebral existence at Abbotsford house mirrored the delineative aspects of Scottish life, language, events, characters, and scenery in the Waverley Novels, making him, in the words of Edinburgh publisher and politician Adam Black a patrimonial figure of cultural Scottishness.

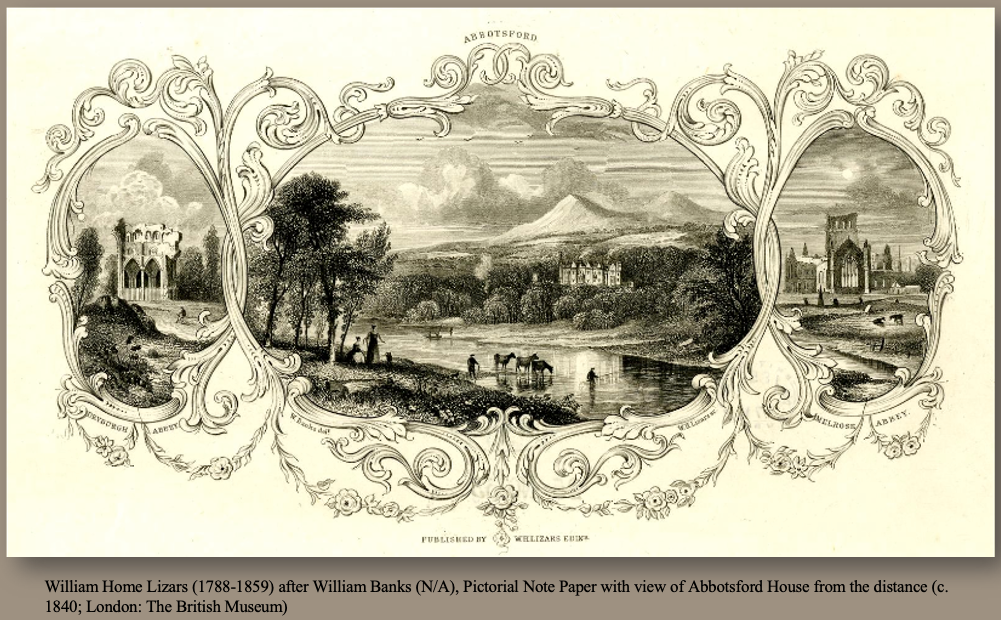

William Home Lizars captures this sense of the nation-forming authority figure in Scott in his decorative etching from 1840, entitled Abbotsford. Here we see pastoral images of Melrose and Dryburgh Abbey – two purportedly unmissable destinations in what Scott called the classic ground of his native homeland – linked in an elaborate pictorial tryptic with Abbotsford house, thus indicating the import of Scott as part of a network of cultural and scopic productions reifying Scottish cultural heritage. Correspondingly, in an 1849 oil painting created by Scottish artist Thomas Faed, an imaginary gathering of Scottish luminaries – from James Hogg, Sir David Wilkie, Adam Ferguson, John Wilson, Henry Mackenzie, and Lord Byron – cluster around the seated figure of the Author Waverley in the centre of the library at Abbottsford house. These figures of literary, historical, and artistic repute appear to confer with the patriarch of Scottish national sentiment, providing a graphic equivalent to the description of John Gibson Lockhart, who, writing in 1837, asserted “whoever had Scottish blood in him, gentle or simple, felt it move more rapidly through his veins when [ . . .] in the presence of Scott.” Abbotsford became the place to pay tribute to this national historical phenomenon, and, importantly, partake in the process of national historical protection and perpetuation Scott championed there through literature.

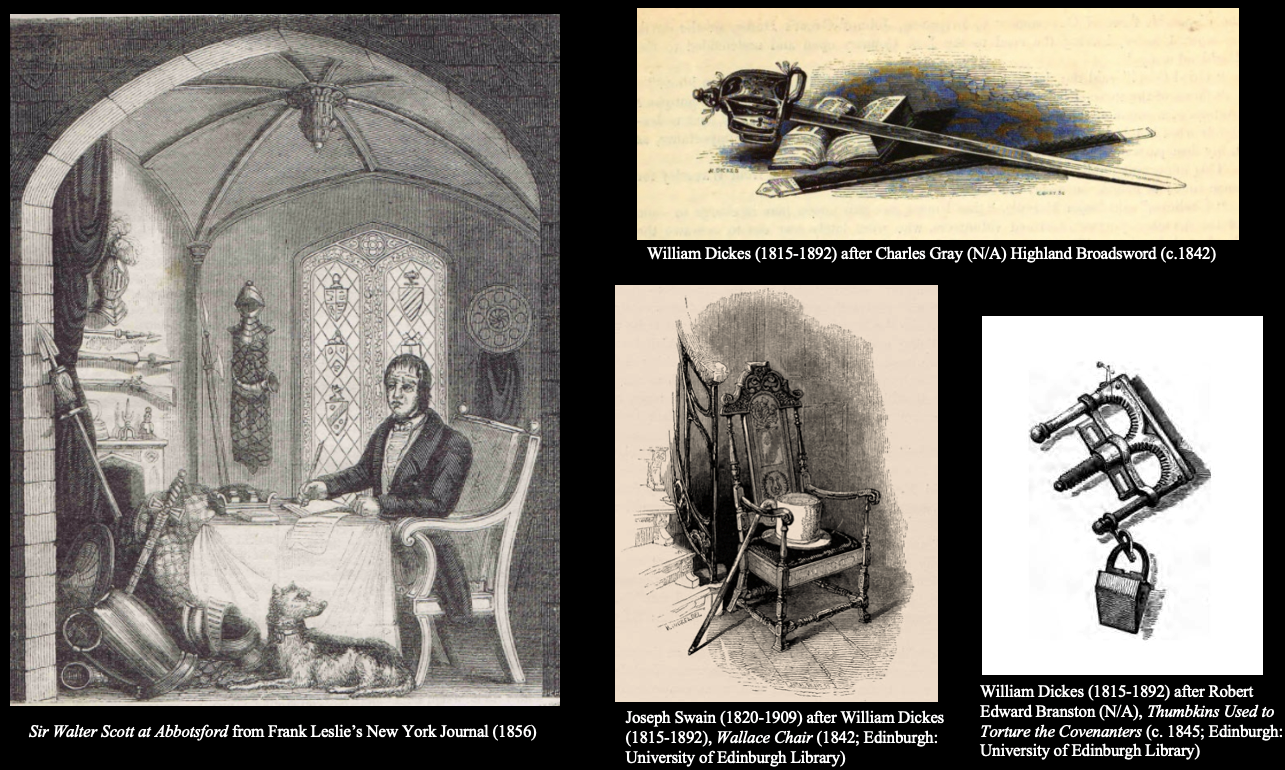

A scan of the art and objectscape of Abbotsford, however brief, reveals a national ethos imbricated in the network of literary and historical associations there. This was by Scott’s design, but over the years it became an integral component to the nineteenth-century construction of his legacy. Images and illustrations of the Scottish collection of art and architecture, personalia, books, and curios at Abbotsford pervaded a variety of artistic genres throughout visual and material culture. The exterior of the house, for instance, appealed to nineteenth-century viewers as a recycling of Scottish heritage items from the Roman occupation in the first century A.D., to the Middle Ages, Reformation, and early modern era. A two-story crenelated gateway and portcullis modelled defensive architecture of the Scottish Border, while notched gable ends, bartizans, clustered chimneys, and whinstone replicated identifiable features of Fyvie, Lauriston, Buchanan, Dunrobin, and Linlithgow castle. Other visible nods to Scottish history included gargoyles and spolia salvaged from recently demolished architectural landmarks in the Border vicinity. Detailed consideration of this material is provided in a series of illustrated wood engravings, produced by the London firm of English printmaker William Dickes. In the image shown at left we see an 1842 illustration of the door of the old Tolbooth of Edinburgh, which adorned a second-story story wall of the eastern facing façade of Abbotsford. This display drew the attention of many, not only for its peculiar placement on the outer reaches of the home, but also for the parallels it bore to the historical content of Scott’s seventh novel The Heart of Midlothian (1818). In another illustration from 1842, shown at right, we see a garden well Scott built out of salvaged bits and pieces from the ruins of Melrose Abbey. The resonance of this work to nineteenth-century viewers lay in its connection to the setting of Scott’s 1805 narrative poem, Lay of the Last Minstrel.

Meanwhile, the interior of Abbotsford house functioned as a purpose-built space for national historical exhibition too. During Scott’s lifetime, this famously object-laden terrain was pegged by nineteenth-century visitors, both real and virtual, as a museum for living in. In the entrance hall, for instance, Scott installed wood paneling from Dunfermline Abbey, marble floor tiles from the Hebrides, animal skulls, mounts, and pelts from the Scottish Highlands, and a grand fireplace modelled after the Abbots Seat of Melrose Abbey. This was joined by coats of arms and shields celebrating eminent Scottish Border clans, and from floor to ceiling, a riot of antiquarian curiosities including a cast of the skull of Robert the Bruce, medieval torture implements, weaponry, and two semi-circular wood presses made out of the fragments of the pulpit of famed Scottish minister and dissenter Ebenezer Erskine. Other public rooms at Abbotsford house such as the armory, library, and drawing room were similarly themed and structured. Scottish history looked out from its walls, observed one nineteenth-century literary tourist, enveloping the modern visitor and providing a means for engaging with the national historical past, not unlike the historical materiality which instilled the Waverley Novels.

It was by this logic that by 1832 Abbotsford attained an institutional footing in Britain comparable to what we now might call a national historical monument or repository. Enclosed within one space, outside of time, and away from susceptibility to neglect, mismanagement, or ruin, the built environment of the home, in nineteenth-century estimation, offered easy access and cultural longevity to the storied remains of Scottish national history. Synonymous with the literary life and practice of the Author of Waverley, it elicited a discourse about the “proud immortality” Scott conferred to art and material artefacts there through the process of fiction writing. In fact, many nineteenth-century literary devotees and visitors to Abbotsford came with the express purpose of donating Scottish heritage items to Scott and the Abbotsford collection – the hope being that, in addition to seeing the place where the Waverley Novels were planned and penned, they could facilitate in its project. The highland broadsword pictured at the top of the slide shown here was given to Scott by the Celtic Society of Edinburgh in 1826. This was joined by an ornately carved chair given to Scott in 1822 by Scottish antiquarian Joseph Train. The provenance of the piece, according to Train, was linked to the scene of the arrest of William Wallace in Robroyston in 1305. Similarly, one Gabriel Alexander sent to Scott a pair of seventeenth-century thumbscrews associated with the Scottish National Covenant. His reasoning behind such a bizarre and grisly gift, he explained in a letter to Scott in 1819, was the author’s status “best and most legitimate custodier [ . . .] of all that is national.” So important was this conception of the body of art and antiquities at Abbotsford, that when Scott faced bankruptcy in 1826, his creditors decided to allow him to keep the house and its collection within a private trust where revenue was acquired from the proceeds of his writing. Abbotsford and the national historical legacy of Scott were, from then on, inextricably linked in the public eye. The author’s home not only symbolized the success its creator had achieved through writing, but also, the service he performed there, collecting, communicating, and safeguarding Scottish cultural heritage for perpetuity.

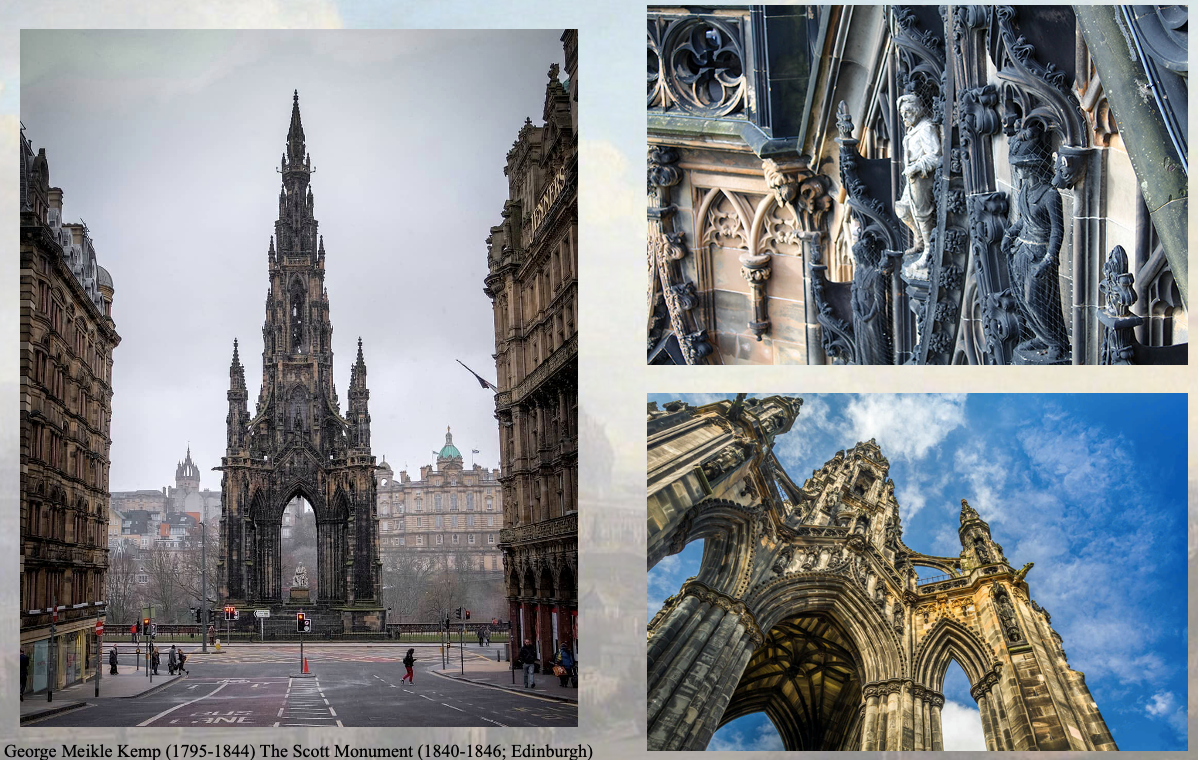

In the years following 1832, this desire to pay homage to the literary life and practice of Scott at Abbotsford fell into decline. Illustrative work and material adaptations of the author’s home remained a steady industry in Britain well into the twentieth century, but the practice of making the physical trek to Abbotsford house, touring its halls, and leaving some mark of readerly admiration there for its author-inhabitant retain and care for lessened. This was due to the fact that Scott was dead and the auratic pull which originally instilled the nineteenth-century experience and understanding of the house and grounds there was gone. To commemorate Scott and, in turn, latch on to the cultural capital of his writing through gift-giving, it was determined that a more durable, more publicly accessible testament to collective pride in the author was needed. Not 10 days of after Scott’s death, on the 5th of October 1832, a gathering of roughly 100 intimates, colleagues, friends, and admirers of the author assembled in the hall of the Royal Institution in Edinburgh and formed a formal committee for “the erection of some lasting monument of gratitude and imperishable esteem . . . for one of Scotland’s most honoured sons.”

It would take another 14 years, countless meeting minutes, a design competition, door to door fundraising, and over £16,000 in subscription fees to create the Scott Monument which resides on Princes St. in Edinburgh, Scotland and to this day, dominates the city landscape. The history and building of this structure is a complex one, and while the ins and outs of its formal configuration certainly provide us with a more palpable sense of the indebtedness nineteenth-century readers, artists, and cultural consumers felt for the literary life and practice of Scott, as I come toward the close of my lecture this evening, I merely want to reflect on its example as a metaphor for the media ecology which shaped Scott’s celebrity. Elements from across the reception history of Scott and the Waverley Novels, for instance, are showcased in the visual and material construction of the Scott Monument. It features 4 separate viewing platforms, a second story chapel and museum space, stained glassed windows, gothic arches, and niches which house the statues of over 64 characters and historical persons illuminated in the Waverley canon. Elsewhere, architectural nods to Melrose Abbey, Roslin Chapel and other prominent Scottish national landmarks featured in the writing of Scott comprise the building, foundation, and tower of the monument. These material components not only recall the rich historical texture and pictorialism which pervaded the Waverley Novels, but also, the impact they had on the reading public in Britain, concretizing cultural Scottishness and effectively bringing its storied material out of obscurity and into view.

In closing, it’s this embodiment of the visual and material imagination which comprised and fed into the cultural phenomenon that was Scott, which, I think, makes the Scott Monument such a compelling testimonial and appropriate place to end my lecture this evening. Sitting at the center of the Monument, under its towering canopy of literary and historical detail is the maud shroud figure of Walter Scott. His statue is twice life-life size and carved in white Carrara marble. Despite the colossal frame and costly material with which this statue towers over the common spectator, there is an element of warmth and approachability to the figure of Scott in this particular representation that is unmistakable. The author, who historian Thomas Carlyle once dubbed King of the Romantics sits in an easy, upright posture, comfortably tucked under his Border tartan with one of his trademark canine companions underfoot. With a closed book in hand, it’s not clear whether Scott has just taken his seat or is momentarily interrupted. One way or the other, he looks up from his reading material, a contemplative expression spread across his face. Looking out over the Edinburgh expanse, and, more broadly, the national and historical terrain before him, the seated Author of Waverley reminds us that it is here, amongst the storied vistas and prospects of the Scottish backcloth – a continuum of historical materiality, old world relics, and living songs – where he is most at home. Taking into consideration the varieties of art, image-making, and media consumption looked at this evening, overlaid with this sweeping prospect, we arrive at a version of Scott not unlike the one with which this lecture began. We see an author who’s creative outpouring defies disciplinary barriers. As the letterpress for the 1871 engraving A Dream of the Waverley Novels suggests, we see a “prodigy of fertility” who leaves in his wake a whole world of romantic incarnations, brilliant, borderless, and great.