Walter Scott sits at the centre of the Scott Monument, surrounded by a city full of stories. Behind him lies Edinburgh’s Old Town, holding a wealth of stories of the city’s past, and looking out towards Edinburgh’s New Town, where stories both present and future were to be found. The monument itself towers over the city, the second largest monument to a writer anywhere in the world- and today, it is both an attraction and something of a navigation point for visitors to the city, as well as a handy, familiar meeting place for Edinburgh residents to meet on the busy, bustling Princes Street. This monument bears testimony to the vast impression Scott and his writings have left upon the city, even almost 200 years after his death; yet, as much as Scott clearly made a vast impression upon the city of Edinburgh, so too has the city made a great impression upon Scott and his writings. In Scott’s stories, the geography, history, reality and fiction of the city of Edinburgh can be found on numerous occasions, overlapping reality and romance, fact and fiction, geography real and imagined. This overlapping is evident even in several titles of works from Waverley to Chronicles of the Canongate. It is this often complex though frequently fascinating relationship with Edinburgh’s history, happenings and stories which surrounded Scott as he lived in the capital, that I wish to explore a little further, and to see how some of these stories take a fictional guise in several novels.

Scenes from the Waverley Novels

On 10th September 2020

Dr Lucy Wood gave us a video tour of sites in the Old and New Towns of Edinburgh connected with Scott.

Lucy Wood is a heritage learning and engagement professional currently working for the Royal Collection Trust at the Palace of Holyroodhouse, and previously for Historic Environment Scotland, The Abbotsford Trust, and The Mavisbank Trust. She gained her PhD from the University of Edinburgh in 2016 with a thesis entitled “Fragments of the Past: Walter Scott, Material Antiquarianism, and Writing as Preservation” (as Lucy Linforth). Her thesis was awarded the Saltire Society’s Ross Roy Medal in 2017, and in early 2018, she held the British Association for Romantic Studies/Wordsworth Trust Early Career Fellowship researching William Wordsworth’s collections at Dove Cottage in Grasmere.

Today, in 'Scenes from the Waverley Novels', Lucy will take us on a tour of the biographical, historical and fictional Edinburgh of Scott's novels. The tour was first delivered as a series of public tours for the Cockburn Association Doors Open Day 2015.

Scenes From the Waverley Novels: Walter Scott’s Edinburgh

Scott Monument

College Wynd

Scott’s earliest years, however, were not to be spent in the city. Scott contracted polio when he was just two years of age, and for this reason he was sent far away from the stench of the city to Sandyknowe Farm in Roxburghshire, home of his paternal grandparents in the Scottish Borders, for good clean air and country living. There, through the stories of his Aunt Jenny and from the very land itself he became immersed in Border ballads and history; tales and traditions which would find their way in abundance his poems and novels, from The Lay of the Last Minstrel to The Monastery. Yet it wasn’t only in the romance of the Borders that Scott felt inspiration could be found- even as a child he discovered that in the city too there were stores of stories waiting to be discovered, if one knew where to look for them.

High School Yards

Through both storytelling and through study, Scott’s school years would have helped to consolidate his probably already significant knowledge of Scottish history- and also through walking. A keen walker from a young age Scott was instructed by his father only to talk as far as would permit him to be away and back within the same day- and so his geographical as well as imaginative rambles were reliant on what the city itself could offer- from tales of the Covenanters or Jacobite stories to more modern day narratives. It was at this time also that Scott began collecting the ‘touch-pieces’ of his fictions- the treasured items connected to Scottish history. In his father’s house in George Square he assembled a collection of ‘out-of-the-way things of all sorts. He had more books than shelves, a small painted cabinet, with Scotch and Roman coins in it … a claymore and Lochaber exe, given him by old Invernahyle, mounted guard on a little print of Prince Charlie; and Broughton’s Saucer was hooked up against the wall below it’ (Life 1.199). Even as a youth, shadows of the Waverly novels yet to come presented themselves to Scott in events, history and in objects.

Edinburgh’s Royal Mile must be one of the most recognisable streets in the world. It is a bold seam stretching all the way from the grand heights of the Castle Rock upon which city’s fortress stands, and right the way down to the foot of the mile and the Palace of Holyroodhouse, where Scott would see King George IV in the first visit of a monarch to Scotland in nearly 200 years. Many of the buildings and features of this famous street have, of course, changed since Scott’s time- for example, we no longer see the Old Tolbooth, the old Edinburgh prison; the Black Turnpike, or Guard House of the city Provost, a building described by Scott as a ‘long black snail’ obscuring the grandeur of the street in front of the Tron Kirk. So too would the High Street have boasted a four-storey tenement of ‘Luckenbooths, or locked booths, a building of market stalls which ran along the north side of St Giles Cathedral, and was demolished in 1817.

The Royal Mile

Despite these changes, in many ways the Mile has kept its distinguishing characteristics for centuries. Indeed, a wonderful description of the Mile can be found in The Abbot, Scott’s 1820 novel set in sixteenth-century Scotland, during the reign of arguably the nation’s most famous monarch, Mary, Queen of Scots. Scott had a very pertinent reason for writing about Mary when he did- having had a rather miserable reception to The Monastery earlier that year, he sought to avail himself of one of the city’s best protagonists, as he outlined in the 1831 preface to the novel, stating:

There occur in every country some peculiar historical characters, which are, like a spell or charm, sovereign to excite curiosity and attract attention, since every one in the slightest degree interested in the land which they belong to, has heard much of them, and longs to hear more… It was with these feelings … that I ventured to awaken, in a work of fiction, the memory of Queen Mary, so interesting by her wit, her beauty, her misfortunes, and the mystery which still does, and probably always will, overhang her history (9-10).

Whilst most of the The Abbot takes place elsewhere in Scotland, including at Loch Leven Castle, the site of Mary’s famous imprisonment, and escape. In the following scene Mary’s young page Roland Graeme arrive in Edinburgh for the very first time. We are treated to a view of the Royal Mile as seen through Roland’s eyes- a view that is recognisable to this day:

The principal street of Edinburgh was then, as now, one of the most spacious in Europe. The extreme height of the houses, and the variety of Gothic gables and battlements, and balconies, by which the sky-line on each side was crowned and terminated, together with the width of the street itself, might have struck with surprise even the more practised eye than that of young Graeme. The population, close packed within the walls of the city, and at this time increased by the number of lords of the King’s party who had thronged to Edinburgh to wait upon the Regent Murray, absolutely swarmed like bees on the wide and stately street. Instead of the shop-windows, which are now calculated for the display of goods, the traders had their open booths projecting on the street, in which, as in the fashion of the modern bazaars, all was exposed which they had upon sale. And though the commodities were not of the richest kinds, yet Graeme thought he beheld the wealth of the whole world in the various bales of Flanders cloths, and the specimens of tapestry; and, at other places, the display of domestic utensils and pieces of plate, struck him with wonder. The sight of cutlers' booths, furnished with swords and poniards, which were manufactured in Scotland, and with pieces of defensive armour, imported from Flanders, added to his surprise, and at every step he found so much to admire and to gaze upon, that Adam Woodcock had no little difficulty in on prevailing him to advance through such a scene of enchantment’ (265-6).

Along with the Mile, Scott it seems was proud of the impressive features of the city- the Salisbury Crags are described with relish on more than one occasion, and in the following excerpt from The Fortunes of Nigel, the servant of Nigel Olifaunt, Lord Glenvarloch, defends the honour of his home city against the suggested superiority of London:

“Come, Jockey, out with it,” continued Master George, observing that the Scot, as usual with his countrymen, when asked a blunt, straightforward question, took a little time before answering it.

“I am no more Jockey, sir, than you are John,” said the stranger, as if offended at being addressed by a name, which at that time was used, as Sawney now is, for a general appellative of the Scottish nation. “My name, if you must know it, is Richie Moniplies; and I come of the old and honourable house of Castle Collop, weel kend at the West-Port of Edinburgh.”

“What is that you call the West-Port?” proceeded the interrogator.

“Why, an it like your honour,” said Richie, who now, having recovered his senses sufficiently to observe the respectable exterior of Master George, threw more civility into his manner than at first, “the West-Port is a gate of our city, as yonder brick arches at Whitehall form the entrance of the king's palace here, only that the West-Port is of stonern work, and mair decorated with architecture and the policy of bigging.”

“Nouns, man, the Whitehall gateways were planned by the great Holbein,” answered Master George; “I suspect your accident has jumbled your brains, my good friend. I suppose you will tell me next, you have at Edinburgh as fine a navigable river as the Thames, with all its shipping?”

“The Thames!” exclaimed Richie, in a tone of ineffable contempt—“God bless your honour's judgment, we have at Edinburgh the Water-of-Leith and the Nor-loch!” (70-71).

Lady Stairs Close

It feels as though any close leading from the Mile could be chosen with the promise of a good story at the end of it- and this one, Lady Stairs Close, gives a feeling of no exception. Part of the magic and mystery of this place comes from the house which stands here- built in 1622 for Sir William Gray of Pittenweem. The House came to be known as Lady Gray’s House after Sir William’s death in 1648, when his wife continued to live there- but it is now known as Lady Stairs House, having changed its name in the early eighteenth century (1719) with a change of resident, Elizabeth, Dowager Countess of Stair. The name of Stair which had, by Scott’s lifetime, been given to this building, was connected with an extremely sad tale, with which Scott was familiar. In the late seventeenth century Janet Dalrymple, daughter of James Dalrymple, Viscount Stair, had fallen in love with and secretly engaged herself to a man named Lord Ruthven. The Dalrymples held Covenanting sympathies; Ruthven was a Royalist. Alas, their secret was discovered, and the unfortunate Janet was forced to marry the choice of her parents, David Dunbar. They were wed on 24th August 1669- the day on which Janet also attempted her husband’s life, suffered a breakdown and from which day she would survive less than a fortnight. The Lady Stairs who gives this house its name was the widow of John Dalrymple, the first Earl of Stair (1648-1707)- brother to the unfortunate Janet.

With good reason, this plot may well sound familiar to the avid-Scott reader – for it is also the plot of Scott’s 1819 novel, The Bride of Lammermoor. In Scott’s novel Janet becomes Lucy Ashton, and Ruthven, Edgar Ravenswood. Scott’s take on the wedding day scene is no less dramatic than the real life events- it is tempting to think that this house and the name it bears would have set Scott’s mind racing with descriptions such as that which follows whenever he walked past:

The instruments now played their loudest strains; the dancers pursued their exercise with all the enthusiasm inspired by youth, mirth, and high spirits, when a cry was heard so shrill and piercing as at once to arrest the dance and the music. All stood motionless; but when the yell was again repeated, all rushed thither to the bridal-chamber whilst the bridal guests waited their return in stupified amazement.

Arrived at the door of the apartment, Colonel Ashton knocked and called, but received no answer except stifled groans. He hesitated no longer to open the door of the apartment, in which he found opposition from something which lay against it. When he had succeeded in opening it, the body of the bridegroom was found lying on the threshold of the bridal chamber, and all around was flooded with blood. A cry of surprise and horror was raised by all present; and the company, excited by this new alarm, began to rush tumultuously towards the sleeping apartment. Colonel Ashton, first whispering to his mother, "Search for her; she has murdered him!" drew his sword, planted himself in the passage, and declared he would suffer no man to pass excepting the clergyman and a medical person present. By their assistance, the bridegroom, who still breathed, was raised from the ground, and transported to another apartment, where his friends, full of suspicion and murmuring, assembled round him to learn the opinion of the surgeon.

In the mean while, Lady Ashton, her husband, and their assistants in vain sought Lucy in the bridal bed and in the chamber. There was no private passage from the room, and they began to think that she must have thrown herself from the window, when one of the company, holding his torch lower than the rest, discovered something white in the corner of the great old-fashioned chimney of the apartment. Here they found the unfortunate girl seated, or rather couched like a hare upon its form—her head-gear dishevelled, her night-clothes torn and dabbled with blood, her eyes glazed, and her features convulsed into a wild paroxysm of insanity. When she saw herself discovered, she gibbered, made mouths, and pointed at them with her bloody fingers, with the frantic gestures of an exulting demoniac (130-132).

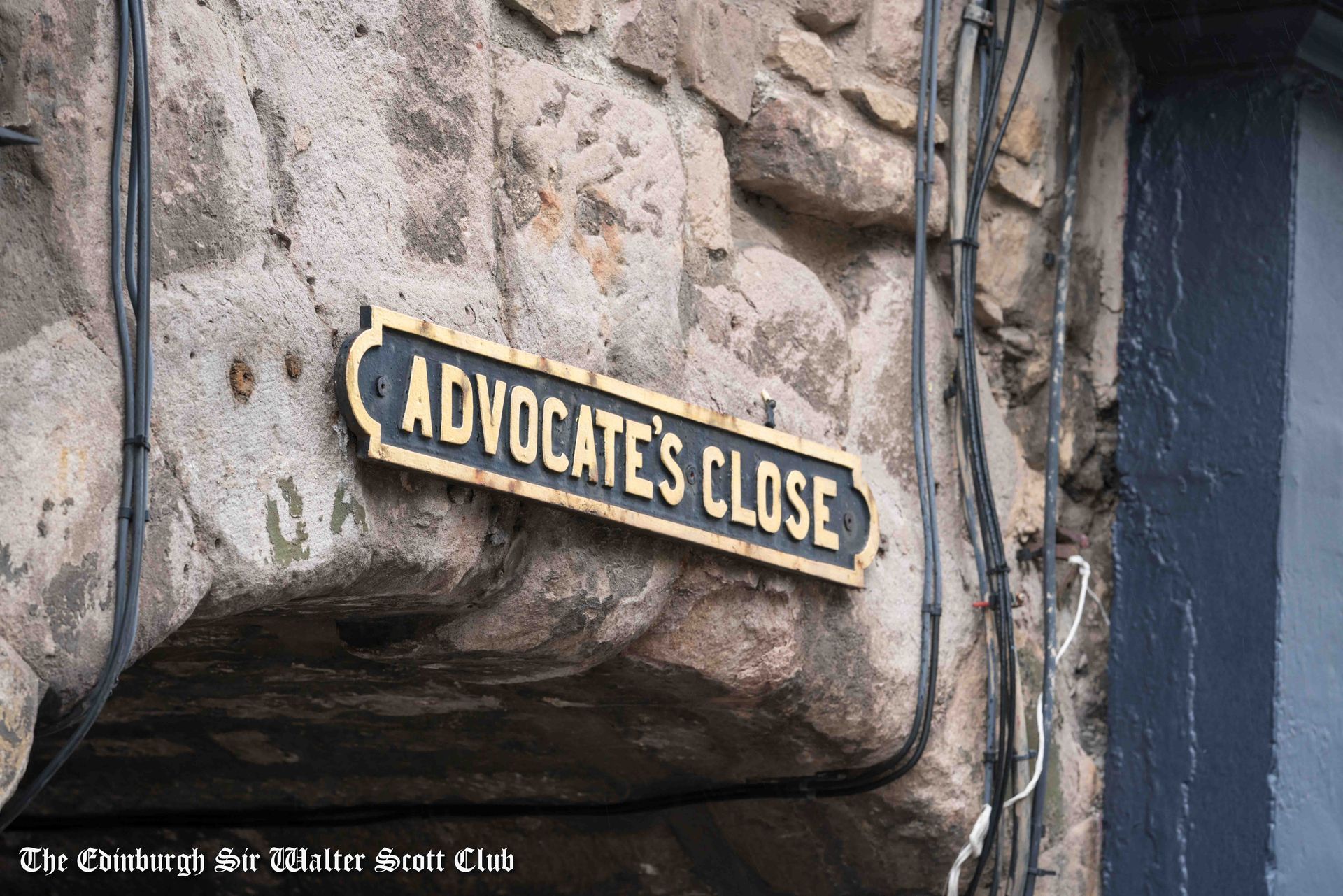

Advocate's Close

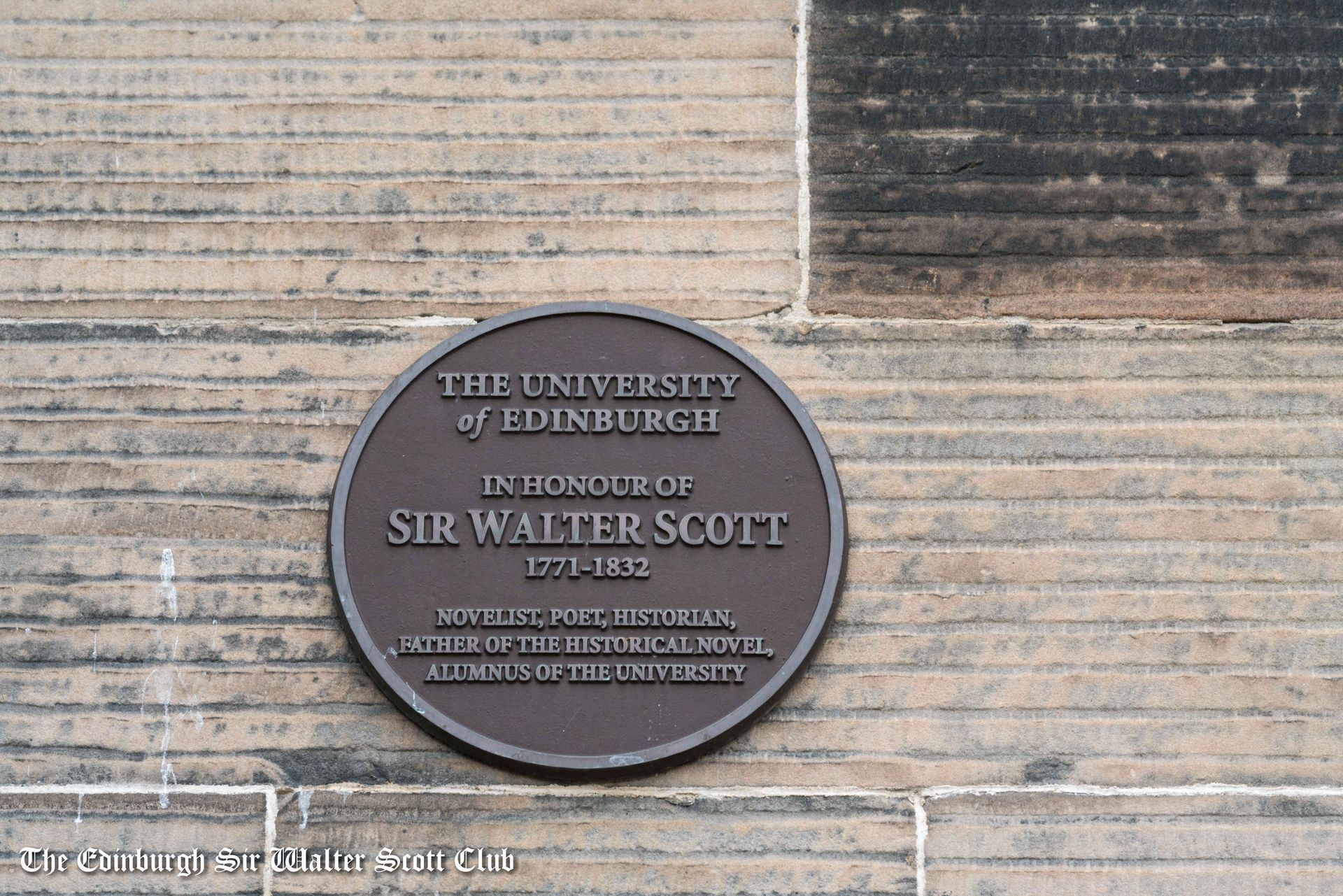

Son of a Writer to the Signet, and himself a man of the law, both in youth and in adulthood Scott would have spent a great deal of time in the legal heart of the city of Edinburgh. One such street is Advocates Close, which takes its name from Sir James Stewart, first Lord Advocate of Scotland, who served between 1692 and 1713. Scott entered the University of Edinburgh at twelve, studying classics and later Scots law under David Hume, nephew of the philosopher. He was apprenticed to his father’s office at the age of fifteen, although this apprenticeship was at several times interrupted by Scott’s abrupt and by all accounts rather worrying growth spurts- for which one doctor proscribed an unwelcome several months of vegetarianism as a cure.

As a young advocate in Edinburgh in the late eighteenth century, Scott would daily have roamed these streets, and made the walk across from the Faculty and Parliament. These streets would have been lined with public houses and taverns of frequently rather questionable status- yet these would be the very inns and rooms within which famous philosophers, lawyers, and writers were to be found conversing, making merry, and much more besides. Scott’s youthful years in enlightenment Edinburgh, amid the hubbub of the law courts and the buzz of societies made him no stranger to this aspect of his gentlemanly profession. An example of what this may have involved appears in a note found in Redgauntlet, describing a daily jaunt to enlightenment Edinburgh institution, John’s Coffee House, once located at the eastern end of Parliament Square, for a bumper-dram of brandy, to be taken promptly at midday, known as the meridian:

This small dark coffee-house, now burnt down, was the resort of such writers and clerks belonging to the Parliament House above thirty years ago as retained the antient Scottish custom of a meridian, as it was called, or noontide dram of spirits. If their proceedings were watched, they might be seen to turn fidgety about the hour of noon, and exchange looks with each other from their separate desks, till at length some one of formal and dignified presence assumed the honour of leading the band, when away they went, threading the crowd like a string of wild fowl, crossed the square or close, and following each other into the coffee-house, received in turn from the hand of the waiter, the meridian, which was placed ready at the bar. This they did, day by day: and although they did not speak to each other, they seemed to attach a certain degree of sociability to performing the ceremony in company.

Parliament Square

Scott was called to office as Advocate in 1792 at the age of twenty one, and retained for the next thirty years of his life, a professional capacity in law. For a good part of that professional life, Parliament House would have been something of a centre. The oldest part of the building is Parliament Hall, completed in 1639, and the Advocates Library, founded in 1682. It stands behind St. Giles Cathedral, once the meeting ground of the great philosophers, lawyers, religious reformers and radicals of Edinburgh. Beneath where we stand is the former Kirk-yard of St. Giles, where the Protestant leader of the Scottish Reformation, and one-time minister of St. Giles John Knox is buried. As the site of so much of Edinburgh’s history, the young Scott would no doubt have been delighted by the imaginative possibilities that opened up to him, when merely winding his way to work. For indeed, in reality the monotomy of the everyday court life did not suit Scott. He found the work to be restrictive- he referred to his profession a ‘prisonhouse’. The vignettes of court life, the intricacies of the cases, and the matters of history, social order, and justice would be of more interest to him than actual practice of law.

Therefore, though they shared a profession there was a dramatic difference between Walter Scott senior and junior, in their expectations and passions. Indeed, it is partly because of his father that Scott wrote so many novels which take their scene as in and around Edinburgh. Walter Scott senior was not a man who took holidays, nor advocated going abroad (ie. outside of Midlothian) for any reason. In fact, he did not even travel to the Borders in 1797 for his son’s wedding. As a young man Scott’s own travels were restricted by the opinions and demands of his father, limited to travel where he could walk to within a day of Edinburgh. Thus many of the city sites, ruins and surrounding areas make up the imaginative content of Scott’s novels.

The relationship between father and son can be read rather closely in pages of Redgauntlet, one of Scott’s novels to be set within legal Scotland. In this novel, young Darsie Latimer becomes the unsuspecting pawn in a plan to lead a (fictional) final Jacobite uprising in 1765, in the name of the, by then rather old Young Pretender, Bonnie Prince Charlie. Darsie’s friend Alan Fairford undertakes to rescue his friend, but in order to do so must escape his father’s plans to launch his son’s legal profession with the case of the eccentric Peter Peeble. Like Scott junior, Fairford is a hard-working, extremely loyal son- like Scott senior, his father is not a man to be trifled with when it comes to the law. Just such a conversation as this one between Alan and his father might have occurred between Scott and his own father, after a long day at work in Edinburgh’s legal centre:

“Alan,” he said, “ye now wear a gown- ye have opened shop, as we would say of a more mechanical profession; and, doubtless, ye think the floor of the courts is strewed with guineas, and that ye have only to stoop down and gather them?”

“I hope I am sensible, sir,” I replied, “that I have some knowledge and practice to acquire and must stoop for that in the first place.”

“It is well said,” answered my father; and always afraid to give too much encouragement, added, “Very well said, if it be well acted up to—Stoop to get knowledge and practice is the very word. Ye know very well, Alan, that in the other faculty who study the ARS MEDENDI, before the young doctor gets to the bedsides of palaces, he must, as they call it, walk the hospitals; and cure Lazarus of his sores, before he be admitted to prescribe for Dives, when he has gout or indigestion—“

“I am aware, sir, that-“

“Whisht—do not interrupt the court. Well—also the surgeons have a useful practice, by which they put their apprentices to work; upon senseless dead bodies, to which, as they can do no good, so they certainly can do as little harm; while at the same time the tyro, or apprentice, gains experience, and becomes fit to whip off a leg or arm from a living subject, as cleanly as ye would slice an onion.”

“I believe I guess your meaning, sir,” answered I; “and were it not for a very particular engagement—“

“Do not speak to me of engagements; but whisht—there is a good lad—and do not interrupt the court.” (241-242)

Laigh Hall

A room within the oldest part of this building makes a direct appearance in Scott’s novel of 1816, The Tale of Old Mortality. Scott draws upon his precise and personal experience of the rooms of this building and chooses the atmospheric Laigh Hall to provide the scene of a particularly grim chapter, describing the room in which the Privy Council of Scotland meet as an ‘antient dark Gothic room, adjoining to the House of Parliament in Edinburgh’ (215-6). Scott draws liberally too upon his imagination to supply details, along with possibly some of the many rather macabre objects from his museum collection. A tense chapter sees protagonist Henry Morton sentenced to exile, and Covenanter Ephraim Macbriar subjected to a sentence far worse:

A dark crimson curtain, which covered a sort of niche, or Gothic recess in the wall, rose at the signal, and displayed the public executioner, a tall, grim, and hideous man, having an oaken table before him, on which lay thumbscrews, and an iron case, called the Scottish boot, used in those tyrannical days to torture accused persons. Morton, who was unprepared for this ghastly apparition, started when the curtain arose, but Macbriar’s nerves were more firm. He gazed upon the horrible apparatus with much composure; and if a touch of nature called the blood from his cheek for a second, resolution sent it back to his brow with greater energy.

“Do you know who that man is?” said Lauderdale, in a low, stern voice, almost sinking into a whisper.

“He is, I suppose,” replied Macbriar, “the infamous executioner of your bloodthirsty commands upon the persons of God’s people. He and you are equally beneath my regard; and, I bless God, I no more fear what he can inflict than what you can command. Flesh and blood may shrink under the sufferings you can doom to me, and poor and frail nature may shed tears, or send forth cries; but I trust my soul is anchored firmly on the rock of ages.”

“Do your duty,” said the Duke to the executioner. (221-222)

Holyrood Palace

The legal aspects of Redgauntlet are, of course, secondary to this main thrust of the work- the fictional Jacobite uprising of 1756. But Redgauntlet was not the first of Scott’s Jacobite works- rather, it was the third, emerging seven years after Rob Roy (1817), and a full decade after the first Jacobite novel- Scott’s first ever novel- Waverley, published in 1814. Scott, as a loyal unionist, suffered a rather head versus heart relationship with Jacobitism, which has lead many to read the ‘wavering’ character of Edward Waverley as reflective of Scott’s own feelings. Waverley, a soldier of the Hanoverian army, finds that he is romantically inclined towards the cause of the Stuart Prince after a protracted stay in the Scottish Highlands where he meets the impressive Fergus McIvor, and his beautiful, passionate sister Flora. Scott’s own great-grandfather, fondly known as ‘Beardie’, had declared that he would neither shave his head nor trim his beard until a Stuart was restored to the Scottish throne- and though Scott was always rather a clean-shaven man, his sentiments in many ways followed those of old Beardie, although his practical support was for the Hanoverian regime. It seems as though Scott gave articulation to this conflict of emotions, in a scene depicting the meeting between Edward Waverley and Charles Edward Stuart, here in the Palace of Holyroodhouse, where the Prince set up court for six weeks in September 1745. Waverley is conducted through ‘a long, low, and ill-proportioned gallery’ to the presence chambers, where he first encounters the Stuart Prince:

A young man, wearing his own fair hair, distinguished by the dignity of his mien and the noble expression of his well-formed and regular features, advanced out of a circle of military gentlemen and Highland chiefs, by whom he was surrounded. In his easy and graceful manners Waverley afterwards thought he could have discovered his high birth and rank, although the star on his breast, and the embroidered garter at his knee, had not appeared as its indications.

“Let me present to your Royal Highness,” said Fergus, bowing profoundly-

“The descendent of one of the most ancient and loyal families in England,” said the young Chevalier, interrupting him. “I beg your pardon for interrupting you, my dear Mac-Ivor; but no master of ceremonies is necessary to present a Waverley to a Stuart.”

He extended his hand to Edward with the utmost courtesy, who could not, had he desired it, have avoided rendering him the homage which seemed due to his rank, and was certainly the right of his birth. 'I am sorry to understand, Mr. Waverley, that, owing to circumstances which have been as yet but ill explained, you have suffered some restraint among my followers in Perthshire and on your march here; but we are in such a situation that we hardly know our friends, and I am even at this moment uncertain whether I can have the pleasure of considering Mr. Waverley as among mine.'

He then paused for an instant; but before Edward could adjust a suitable reply, or even arrange his ideas as to its purport, the Prince took out a paper and then proceeded:— “I should indeed have no doubts upon this subject if I could trust to this proclamation, set forth by the friends of the Elector of Hanover, in which they rank Mr. Waverley among the nobility and gentry who are menaced with the pains of high-treason for loyalty to their legitimate sovereign. But I desire to gain no adherents save from affection and conviction; and if Mr. Waverley inclines to prosecute his journey to the south, or to join the forces of the Elector, he shall have my passport and free permission to do so; and I can only regret that my present power will not extend to protect him against the probable consequences of such a measure. But,' continued Charles Edward, after another short pause, 'if Mr. Waverley should, like his ancestor, Sir Nigel, determine to embrace a cause which has little to recommend it but its justice, and follow a prince who throws himself upon the affections of his people to recover the throne of his ancestors or perish in the attempt, I can only say, that among these nobles and gentlemen he will find worthy associates in a gallant enterprise, and will follow a master who may be unfortunate, but, I trust, will never be ungrateful.” (95-96).

The Heart of Midlothian

The heart-shaped, tiled mosaic which can be found on the ground in front of St Giles Cathedral marks what was once the entrance to The Heart of Midlothian, or, the Old Tolbooth prison of Edinburgh. Built in the fifteenth century, the Tolbooth of Edinburgh was a grim and gruesome place. The building itself would have obscured the view that we have today, protruding out into the middle of the Royal Mile with its bulk. On the western side, parallel to the front of St. Giles here, a further section was built at a significantly lower level. This was the execution platform; before this public executions had most often taken place at the Mercat cross, on the other side of the cathedral. But the mounted platform created a theatrical stage-like effect for the execution, which was even in the eighteenth-century regarded as a form of spectacle. Even some forms of torture involved chaining prisoners outside of the prison, as in a pillory- and often the heads of the most notorious prisoners would be pitched upon a spike outside the prison, extremely visible to all that passed. When the Tolbooth was eventually demolished in 1817, great crowds assembled in order to witness the fall of this infamous building. Scott was among these spectators, having already ensured his possession of several relics of the day including the great oak door of the prison, which he built high upon a wall at Abbotsford, his home in the Scottish Borders; two great iron locks, and the gigantic set of keys.

These objects, and the prison’s dramatic history, certainly resonated with Scott as within a year of the prison’s demolition, his novel of the same name, The Heart of Midlothian, was published in 1818. The novel follows the plight of Jeanie Deans and her younger sister, Effie, accused of infanticide. Unmarried, there is a strong suspicion that Effie had concealed her pregnancy and murdered her child in order to conceal her then considered sexual impropriety- yet, pitying the young and beautiful girl, the officials offer Effie a final life-line. If she can prove that she had communicated her pregnancy to someone- to the person closest to her- she might avoid the death that awaits her. The person who might offer her deliverance is her elder sister Jeanie; yet Jeanie, daughter of a staunch Cameronian, and innately moral, cannot tell the lie that will save her sister, and instead confesses ‘Alack! Alack! She never breathed word to me about it’. Yet Jeanie is not the heartless sister that you may now think. Demonstrating not only empathy and humanity, but also intricate knowledge of Scottish law, whilst Effie languishes in the Old Tolbooth of Edinburgh, Jeanie journeys on foot to London, some four hundred miles, in order to seek a royal pardon. Meeting with Queen Caroline, Jeanie makes the following appeal to Her Majesty’s sensitivity, thinking all the while of her sister languishing here inside the desperate walls of the city Tolbooth:

My sister, my puir sister, Effie, still lives, though her days and hours are numbered! She still lives, and a word of the King’s mouth might restore her to a brokenhearted auld man, that never in his dailty and nightly exercise, forgot to pray that his Majesty might be blessed with a long and prosperous reign, and that his throne, and the throne of his posterity, might be established in righteousness. O, madam, if ever ye kend what it was to sorrow for and with a sinning and suffering creature, whose mind is sae tossed that she can be neither ca’d fit to live or die, have some compassion on our misery!- save an honest house from dishonour, and an unhappy girl, not yet eighteenth years if age, from an early and dreadful death! Alas! it is not when we sleep soft and wake merrily ourselves that we think on other people’s sufferings. Our hearts are waxed light within us then, and we are for righting our ain wrangs and fighting our ain battles. But when the hour of trouble comes to the mind or to the body- and seldom may it visit your Leddyship- and when the hour of death comes, that comes to high and low- lang and late may it be yours! – Oh, my Leddy, then it isna what we hae dune for oursells, but what we hae dune for others, that we think on maist pleasantly. (214-215)

Grassmarket

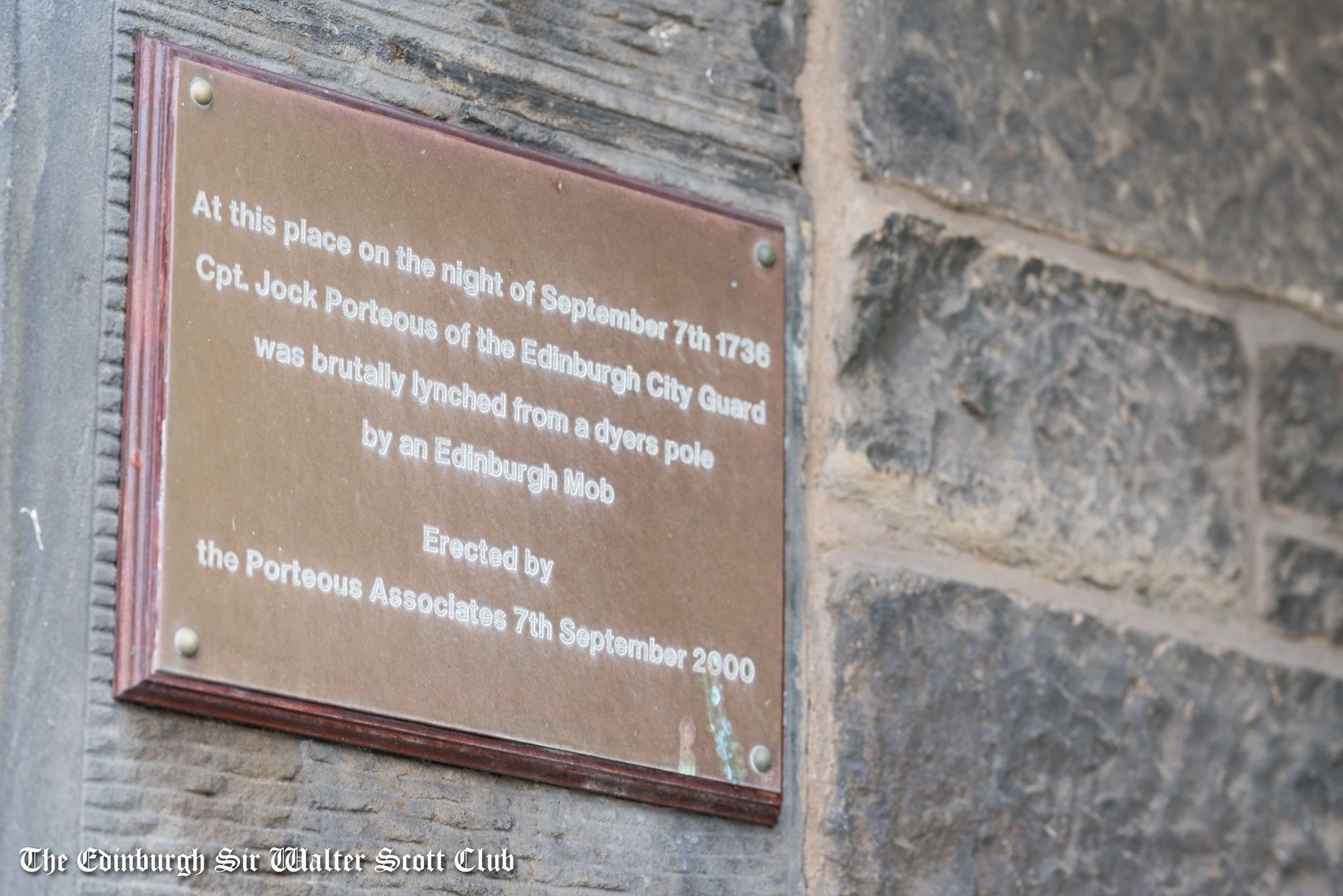

Effie’s plight and Jeanie’s journey emerged from a real story related to Scott- not an Edinburgh story, but, being from Dumfries, not too far away. It was communicated to Scott by a Helen- Mrs Helen Goldie, wife of Thomas Goldie- and was about a Helen, Helen Walker, who in Scott’s novel becomes Jeanie Deans. Scott’s fictionalised rendering of this real tale collides with another real story a particularly infamous Edinburgh story, belonging to the Old Tolbooth. For Scott opens his novel with an account of the Porteous riots, events of which took place in 1736. Events began when two ‘housebreakers’ or thieves, named Wilson and Robertson, who had been tried and found guilty, were awaiting execution at the Old Tolbooth. They made a final attempt to escape by filing down the iron bars of their cell- but the plan was thwarted by the larger of the two men, Wilson, who attempted to squeeze his way out first, ignoring Robertson’s suggestion that he, smaller and more lithe, should go first and then render assistance from the outside. Wilson felt the guilt of his mistake and so made a plan of his own, to save his accomplice from the fate of execution by accosting the executioner at the critical moment. He did just that and Robertson escaped- but Wilson was still to be executed. Responding to rumours that a rescue mission was afoot for the heroic Wilson, the order was put out that the City Guard should attend the execution, armed, under the command of Captain Porteous. When the time came, Wilson’s execution was awaited with baited breath, and attended by thousands; and under the watchful eye of Porteous, the execution went ahead. Afterwards, tensions mounted, and unrest followed- culminating in the open fire of the City Guard, and the death of a number at the scene. Incensed by the opening of fire upon the crowd, the people demanded justice, and later that same day Porteous was imprisoned- somewhat ironically in the Tolbooth- and charged with murder. Such was the feeling in the city that before the sentence of the law could be carried out, a crowd stormed the Old Tolbooth where Porteous was imprisoned. What followed is best described by Scott himself- reality and fiction collide as Porteous is borne down from the prison through the West Bow, and to the Grassmarket, and clergyman Reuben Butler, Jeanie’s fiancé, is called upon to give him last rites to the man, witnessing in the process the following, menacing scene:

The procession now moved forward with a slow and determined pace. It was enlightened by many blazing, links and torches; for the actors of this work were so far from affecting any secrecy on the occasion, that they seemed even to court observation. Their principal leaders kept close to the person of the prisoner, whose pallid yet stubborn features were seen distinctly by the torch-light, as his person was raised considerably above the concourse which thronged around him. Those who bore swords, muskets, and battle-axes, marched on each side, as if forming a regular guard to the procession. The windows, as they went along, were filled with the inhabitants, whose slumbers had been broken by this unusual disturbance. Some of the spectators muttered accents of encouragement; but in general they were so much appalled by a sight so strange and audacious, that they looked on with a sort of stupified astonishment. No one offered, by act or word, the slightest interruption …

As they descended the Bow towards the fatal spot where they designed to complete their purpose, it was suggested that there should be a rope kept in readiness. For this purpose the booth of a man who dealt in cordage was forced open, a coil of rope fit for their purpose was selected to serve as a halter, and the dealer next morning found that a guinea had been left on his counter in exchange; so anxious were the perpetrators of this daring action to show that they meditated not the slightest wrong or infraction of law, excepting so far as Porteous was himself concerned.

Leading, or carrying along with them, in this determined and regular manner, the object of their vengeance, they at length reached the place of common execution, the scene of his crime, and destined spot of his sufferings. Several of the rioters (if they should not rather be described as conspirators) endeavoured to remove the stone which filled up the socket in which the end of the fatal tree was sunk when it was erected for its fatal purpose; others sought for the means of constructing a temporary gibbet, the place in which the gallows itself was deposited being reported too secure to be forced, without much loss of time. Butler endeavoured to avail himself of the delay afforded by these circumstances, to turn the people from their desperate design. (126-127)

Edinburgh Castle

It was, upon rediscovery in 1819, over one hundred years since the sceptre of Scotland had performed its final duty- after which it had been deposited in a strong box in the chest of an uncertain location in Edinburgh Castle, along with the other items making up the Honours of Scotland. This was not the first chapter in their rather thrilling history- rather, the story of the Honours spanned over the centuries, with chapters spent concealed within the walls of Dunottor Castle, or buried under the floor of Kineff Parish Church. With intrigue at each turn, from usurpation, concealment, interment- the tale of the Honours of Scotland might be described as a gothic plot of national proportions.

However, though it is tempting to think that the Honours spent a century in greatest secrecy hidden away in a remote and unknown corner of the Castle- in reality it was well known where they were. Yet in the course of a century it took the curiosity and impulse of Scott alone to bring them to light once more for the nation. He brought a petition to the then Prince Regent and future king George IV to carry out the expedition, which was begun on 4th February 1818, to bring forth the Honours from their concealment. Furthermore, as well as leading the rediscovery, Scott did communicate this true Edinburgh tale to the Scottish people in two publications- the Description of the Regalia of Scotland (1819) and also in his Provincial Antiquities and Picturesque Scenery of Scotland (1826).

It might seem strange that this most fantastic of all Edinburgh tales was never to become a Waverley novel. Yet perhaps it was an occasion upon which Scott found fact to be rather stranger than fiction- it was also a moment, perhaps, where Scott saw that rather than writing Scotland’s history into his fiction, he could effectively write himself into Scotland’s history by giving himself a prominent place in such a tremendous story. And, standing on the castle esplanade, surveying the city, with a spectacular view of the Scott monument and the sites of his stories surrounding you from every side, it is not hard to see how much he remains written into the very fabric of the city to this day.

Text: Dr. Lucy Wood

Filming and Photography: Lee Live

Video Production: James Parsons

Readers: Fiona Johnston, Richard McLauchlan, William Stewart, Michael Wood