Macpherson, Burns and Scott: Driving Visual Art

Thursday 23rd September 2021

Summary of the Talk

Key Themes:

- How Scottish literary figures—Macpherson, Burns, and Scott—influenced the visual arts in the 18th and 19th centuries.

- The development of a “national landscape” in Scottish art.

- Artistic responses to these literary figures by prominent artists, especially Alexander Nasmyth, J.M.W. Turner, David Wilkie, William Allan, and D.O. Hill.

- The role of steel engraving and mass publication in disseminating these images to a broad public.

Key Takeaways

1. Scott as a Bridge Figure:

- Scott’s work built on and responded to the earlier literary visions of James Macpherson’s Ossian and Robert Burns.

- He was influenced by both: Macpherson’s mythic landscapes and Burns’s lyrical evocations of rural life.

2. Turner’s Deep Engagement:

- J.M.W. Turner created around 80 illustrations for Scott’s works.

- He emphasised “spirit of place,” often depicting Scott’s landscapes with small human figures to foreground nature’s majesty.

- Turner’s early Ossian-inspired painting (1802) predates his collaboration with Scott.

3. Alexander Nasmyth’s Role:

- Personal friend of both Burns and Scott.

- Created the iconic portrait of Burns.

- His landscapes helped construct a visual language for Scottish nationalism.

4. Art and Print Culture:

- Steel engraving enabled mass circulation of art tied to Scott and Burns.

- Edinburgh’s William Miller was a key engraver, praised by John Ruskin as Turner’s finest.

5. International Influence:

- Ossian was translated into several European languages and inspired Goethe and Napoleon.

- Turner and other British artists contributed to shaping not only a Scottish but a European sense of "national landscape."

6. Visualising Urban Scotland:

- The romanticisation of rural Highland landscapes was balanced by interest in urban scenes, such as Nasmyth’s depiction of the Tollbooth and Edinburgh’s redevelopment.

- These works reflect the Enlightenment's tension between tradition and progress.

7. Art Education in Scotland:

- The development of institutions like the Trustees’ Academy in 1760 created a context for Scotland’s artistic blossoming.

- The Royal Scottish Academy and earlier schools (e.g., Foulis Academy in Glasgow) played foundational roles.

Noteworthy Insights

- The concept of "landscape as literature" emerged during this period—scenery became emblematic of national identity.

- The human presence in these landscapes, even if minimal, was crucial. Figures provided scale, emotion, and connection.

- The haunted, poetic aura of the Scottish landscape—what Macdonald called “Caledonia, stern and wild”—became central to both art and literature.

- Patrick Geddes’s legacy, especially regarding cross-cultural revivalism in India and Japan, was briefly acknowledged, showing the reach of Scottish intellectual influence.

Murdo Macdonald is author of Scottish Art (Thames and Hudson, 2000; new edition 2021), Patrick Geddes’s Intellectual Origins (Edinburgh University Press, 2020), and Ruskin’s Triangle (Ma Biblithèque, 2021). His most recent chapter is ‘Robert Burns and the Visual Arts’ in The Oxford Handbook of Robert Burns, (Oxford University Press, 2024). He is an honorary member of the Royal Scottish Academy, and an honorary fellow of the Association for Scottish Literature. He is professor emeritus of History of Scottish Art at the University of Dundee, Scotland.

Selected images from the presentation are shown below

Introduction by Dr. Lucy Wood:

Our lecturer this evening is Professor Murdo Macdonald, Emeritus Professor of History of Scottish Art at the University of Dundee. He is the author of Scottish Art in the Thames and Hudson series—a book many of us will know and value. Alongside Will Maclean and Arthur Watson, he developed the practice-led PhD programme in Fine Art at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design.

Professor Macdonald’s research interests span Highland art, Gaelic culture, Robert Burns, the Celtic revival, and the polymath Patrick Geddes. He is also noted for his long-standing engagement with James Macpherson’s Ossian. In 2013, he and Eric Shanes identified J.M.W. Turner’s lost Ossian painting from 1802.

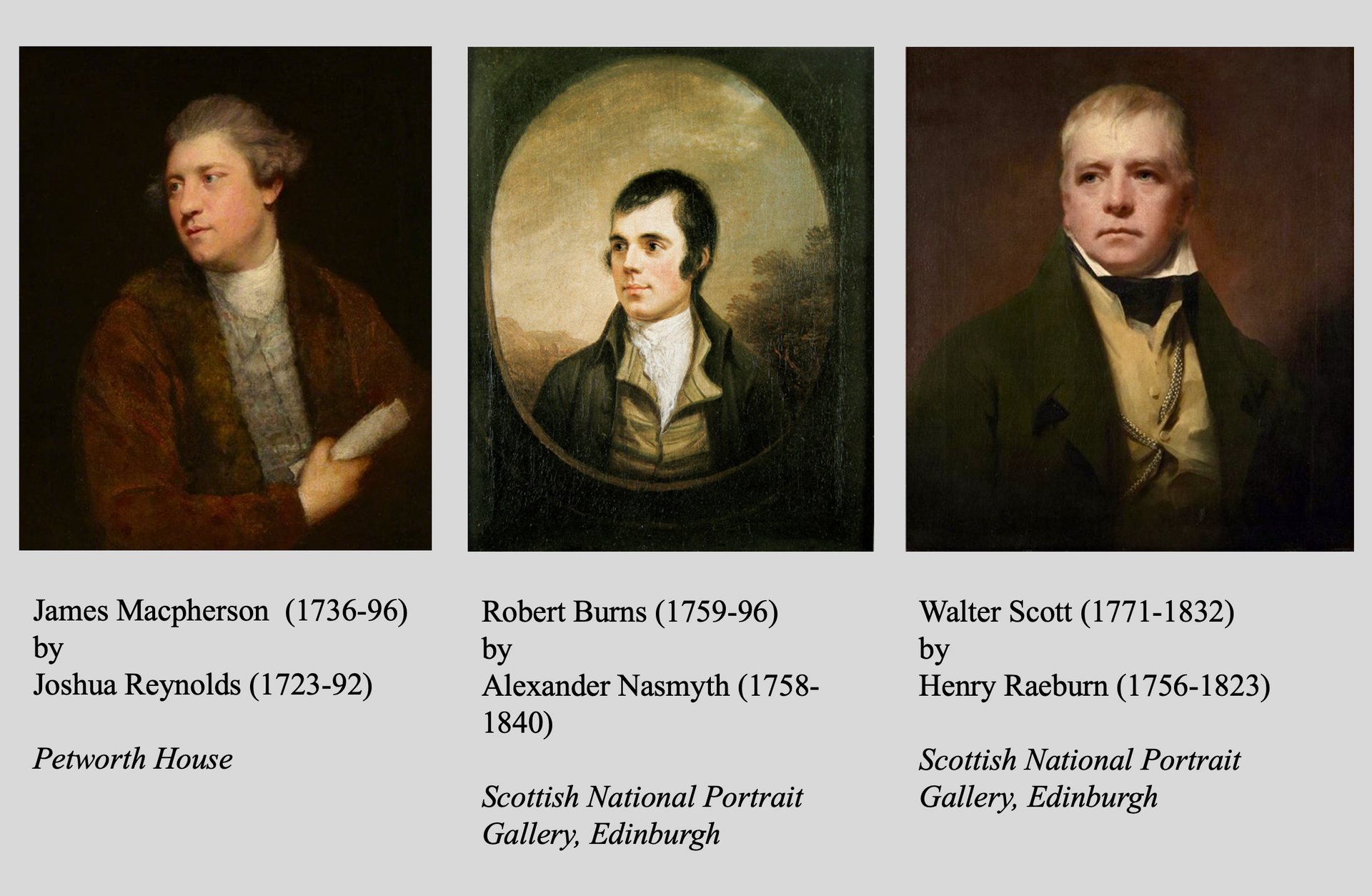

Synopsis: My talk gives context to the literary work of Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832), from the perspective of visual art. Scott is too easily credited as the point of origin for the creation of the image of Scotland, but inspection of visual art reveals that this is far from the case. Crucial to my presentation is the discussion of art produced before Scott himself was active, for it sets the literary and artistic scene, providing the background we need to understand art that responds more directly to Scott. In particular, I note art made in response to the work of James Macpherson (1736-96), and Robert Burns (1759-96), the two dominant figures of Scottish literature of the generations immediately before Scott. James Macpherson was born thirty-five years before Scott. He had completed his major literary contributions by 1773. Those contributions began with Fragments of Ancient Poetry in 1760, then Fingal in 1762 and Temora in 1763. Those works came together in The Works of Ossian in 1765. They were re-edited as The Poems of Ossian in 1773. Scott was born in 1771 so we can consider him – literally – as a child of the Macphersonian age in Scottish literature. And Scott was a teenager of the Burnsian age, having the good fortune to meet Robert Burns at Adam Ferguson’s house in Edinburgh in the winter of 1786-7. Scott was fifteen at the time and Burns would have been in his late twenties.

A particular focus is work by artists who engaged either with the work of Macpherson or that of Burns, but who subsequently made a significant contribution to imagery related to Scott also, bridging the literary gap, so to speak. Two artists fall firmly into that category. Firstly, the Scottish artist Alexander Nasmyth (1758-1840) who engaged with both Burns’s work and later with that of Scott; he was a friend of both writers. Secondly, the English artist J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) who made an important work in response to Macpherson’s Ossian in 1802, and later made a major contribution to illustrating Scott. Like Nasmyth, Turner knew Scott.

Alexander Nasmyth was about thirteen years older than Scott. He was one of the key Scottish thinkers of his day. He was primarily a painter, most well-known today for his portrait of his friend Robert Burns, but he was also a pioneer of Scottish landscape painting, including remarkable illustrations responding to Burns’s poetry. He was also an engineer, and an architect – not least of Saint Bernard’s Well in the New Town. That neoclassical temple dates from 1789, two years after his portrait of Burns, so it would have been very much part of the Edinburgh that Walter Scott experienced as a young man. In due course Scott and Nasmyth became friends, and the older painter was something of a mentor for the young writer.

Turner was a close contemporary of Scott, born in 1775, only four years after Scott himself. He was also an artist capable of matching Scott’s own greatness, both in technical terms and with respect to their shared European vision. That matching finds a direct expression in the numerous watercolours he made to be engraved as illustrations for Scott’s work. Of particular interest are those made in the period just before and just after Scott’s death. But the wider the wider context I draw attention to here is indicated by the fact that Turner’s response to James Macpherson’s Ossian was much earlier. Dating from 1802, its full title is Ben Lomond Mountains, Scotland: The Traveller - Vide Ossian's War of Caros. It was made significantly before Scott’s seminal Highland poem, The Lady of the Lake, which was published in 1810.

The beginning of The Lady of the Lake is itself a reworking of the end of Macpherson’s Berrathon (published, in 1761, in Fingal and other poems by Ossian,), and looking at that link between Macpherson and Scott from the point of view of visual art is informative. The work of Alexander Runciman (1736-85) in the 1770s enhances understanding of this through the importance of nature in his Ossian compositions, his vision prefiguring what Scott would later call ‘Caledonia stern and wild’. Runciman’s response to Ossian, along with that of his younger contemporary Charles Cordiner (1746-94), points the way to a view of Scotland as an iconic landscape imbued with legend and history, essentially a literary landscape. In the response to Macpherson in the 1770s one can thus see art that references literature beginning to drive the idea of a national landscape for Scotland. In due course artists responding first to Burns and then to Scott would develop that further.