Reminiscences of Sir Walter Scott

Introduction by Bridget Falconer-Salkeld

Agnes Cunningham (1807–1893) was a twin daughter of John Usher, Third and last Laird of Toftfield (1766–1847) and his second wife, Agnes Blaikie (1779–1850) of Langhaugh, Galashiels, whom he married in 1802.[1] Her first recollection is of the celebrations held at Toftfield to mark the allied victory at the Battle of Waterloo on Sunday, 18th June 1815. At the time, Agnes Usher (born 19th October 1807) was in her eighth year and resided with her parents and numerous siblings at Toftfield, later Huntley Burn.

To set this memoir in context, its tone can safely be said to reflect contemporary public opinion, and it is clear that in compiling her reminiscences Agnes Cunningham drew on Lockhart’s Memoirs.[2] But there were contrary voices in the public sphere, notably John Ruskin’s strongly expressed opinions of Abbotsford, both inside and out — he loved the Works and never travelled without them, but deplored the work of the builder of Abbotsford. The conference paper by Julie Lawson, “Ruskin on Scott’s Abbotsford” is a valuable critique that provides the proper balance.[3]

Agnes Cunningham’s memoir is undated, and may be a compilation, but from textual inference it can be dated, at least in part, as late as ca. 1891, about sixty years after the death of Sir Walter Scott in 1832.

The seven-page typescript of the original holograph was made by retired veterinary surgeon Miss Jean Margaret Pinkney (1919–2015, BVMS, Glasgow), the friend since infancy of my late husband, Robert Salkeld, FLCM, ARCM. It was among a sheaf of papers she passed to the present writer in 2012 with a view to publication in any suitable medium. A note about Jean Pinkney, known by us as JP: she was of the House of Usher on the distaff side; Agnes (Aggie) Cunningham, née Usher, writer of the memoir, was her great-great- aunt. Agnes’ twin sister Mary Menzies, née Usher, the younger of the two, was JP’s great-great-grandmother. JP’s mother, Jessie Usher Menzies (1881–1972) married William Ferrier Taylor Pinkney (1883–1962, FRPS), and through her father, JP was descended from Francis Mcnab, 16th Chief of Clan Mcnab (1753–1816), well-known for his colourful life and his portrait by Raeburn.[4]

The memoir is here presented unabridged. A few silent corrections have been made; punctuation has been mostly retained and only occasionally cleaned up.

The first event I remember is the Great Battle of Waterloo and the grand bonfire in celebration of it on my father’s property, and in the course of the following year, the death of my grandfather through which my father became possessed of Toftfield and from that time was called the Laird. This possession was one to be proud of, having been in the family of the Ushers for three hundred years [sic],[5] consisting of 600 or 700 acres of arable land and a wide extent of moor or pasture and very prettily situated.[6] The house was old and insufficient for a growing family and my father in 1816 had built a good substantial new one just complete and ready for our occupying. I must at this stage have been in my ninth year.

Sir Walter’s fame as a great poet had been growing from the beginning of the century, but not as a novelist until 1814 nor was he created a Baronet until 1820, so he was only known to us as “the Shirr”, viz. “Sheriff of Selkirkshire” to which he had been appointed about 1800, and we only knew him by sight as he drove in a large old–fashioned yellow carriage to and from Melrose Abbey. He had from boyhood a great desire to possess land. His first purchase was in 1811 — a hundred acres of very poor land bordering on the Tweed, three miles from Melrose, with only a miserable cottage upon it named Clarty Hole, but prettily situated. His quick eye saw its possibilities and with his taste for planting and Mrs Scott’s for gardening, it soon assumed a very attractive aspect. The cottage was largely added and formed a commodious temporary home for five years, as well as a most convenient post of observation from which to superintend the building of his far–famed baronial mansion, Abbotsford.

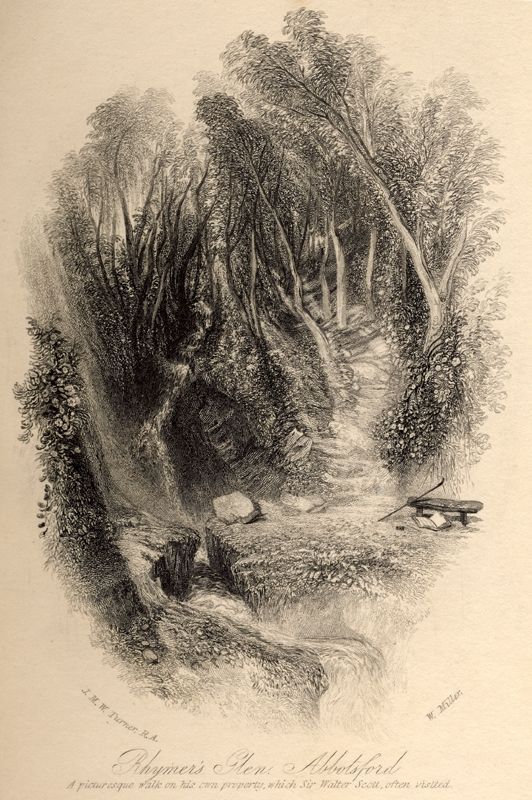

It was in this little modest home Sir Walter spoke of having spent the happiest portion of his life, with his wife and young family around him, in the midst of the simple domestic enjoyments he prized so much and before the great tax upon his celebrity claimed so much of his time and hospitality. As in after years, it was here too, these marvellous creations of his brain, his romances, were first given to the world. Waverley had been written some years previously, but not meeting with his own approval, had been withheld till then, and was received with such universal admiration that it was followed in the course of twelve months [sic][7] with six of his best novels creating a perfect furore of excitement in Melrose and the neighbourhood, never allowed to get into the library, but handed from house to house, and the shortest possible time given for their perusal. No wonder that he was stimulated to a great ambition for land. Since his first purchase he had been gradually extending his possessions principally for planting purposes till it closely bordered on my father’s pretty property, and to own it became the great desire of his heart. I can see that to him it possessed attractions far beyond its intrinsic value: first, its near proximity to what he had; second, at its western extremity was a beautiful though small loch [Cauldshiels Loch], famous for trout fishing — he admired, and used often to drive to it with friends for that sport. From this issued a little burn flowing through a deep romantic glen called Rhymer’s Glen. This Sir Walter set great store by, as the scene where in long past ages a wizard called Thomas the Rhymer used to meet with the Queen of the Fairies, and lastly the greatest attraction of all, the good and substantial house so recently built on the estate. He saw in this the fulfilment of one of the fondly cherished desires of his life.

In his school days he had formed a lasting friendship with three sons of a Professor Ferguson [Dr Adam Ferguson (1723–1816)].[8] They had chosen a military profession and after long absence from Scotland, and in prospect of returning home, had written to Sir Walter requesting him to find a house for them in the neighbourhood of Abbotsford. This was no easy matter, considering their requirements, for they were unique as a family both as regards character and numbers, consisting at that time of three bachelor brothers and three old maiden sisters.[9] The former, Sir Adam Ferguson [1770–1854], Captain John [R.N.] and Colonel James all loved like very brothers and sisters, and few pages of his diary but contained some reference to them such as “Went to Huntly Burn to breakfast”, or “The Fergusons dined at Abbotsford” — and it was there that the only house with all the necessary accommodations was found, at Toftfield.

I ought to have named much sooner that my father had made Sir Walter’s acquaintance soon after he came to our near neighbourhood and was honoured by his friendship, this being fostered by their mutual love for greyhound coursing, and my father being famed for his good greyhounds, the annual Abbotsford Hunt being one of the great sporting days, when all the party, including the Ettrick Shepherd [James Hogg (1770–1835] and other celebrities, were present. My father always sent a splendid haunch of Wedder mutton for the occasion, which was proclaimed to be the best of the season.[10] As this feast occurred when the seven rummers of whisky toddy was the prevailing custom in Scotland after dinner,[11] you can imagine the jollification was kept up till a late hour, and the guests not in a fit condition to ride home with safety. On one occasion when my father was to dine with Sir Walter, my mother pinned up the tails of his coat to prevent them catching any white hairs from the grey horse he rode, warning him to ask someone to let them down before going into the drawing-room, but to her dismay he came home as he left without having remembered anything about them, which no doubt was looked on as a good practical joke.

It is more than time I should come to some more personal relation to Sir Walter Scott, when he first appeared in our family circle, and though too young to understand the reason, or give the exact date, it must have been when he was in treaty with my father for the purchase of his property in 1816. Yet it does not seem to have been finally settled till pretty far on in 1817 — when it is intimated to his intimate friend and publisher, J. Ballantine, in these terms: “I have just become a great Laird, having closed with Usher for his beautiful patrimony Toftfield.

It was in this intermediate time that we, as children, saw most of Sir Walter. My father being often out of the way when he came, it was his custom to come into the house to have a chat with my mother till he was found. He very soon won our hearts by his charming and kindly ways with us. He had a great love for children, telling them little stories, and had the power of drawing out what intelligence they might possess. He was much taken with our little precocious brother John,[12] then only five years old, and encouraged him to sing and repeat little bits of poetry, which no doubt tended to develop what has been a ruling passion of his life — poetry and song.

At the present time, in his eighty-third year, he is preparing for publication a volume of nearly eighty pieces of his own composition. I think the great interest Sir Walter took in [my sister] Mary (later Mrs [George] Menzies) and myself was our being twins and so exactly like each other that he never learned to know the one from the other. We too used to sing to him and pleased him as he remarked we had a correct ear for music, and asked my father if we had been taught. My father having answered in the negative, but added, “I have just engaged their first governess and must get a piano.” Sir Walter offered to send one his daughter had been taught from, as he said it was standing of no use at Abbotsford, which we accepted and thus the precious relic came into our possession. In course of years it also became useless to us, yet though no longer dispensing sweet music it had an honoured place in our home through many changes, and came into my sole possession after the death of my father and mother, simply because I was the first to put in a claim for it, and as an heirloom in the family I presented it to my eldest daughter, Mrs Crudelius, on her marriage ten years ago [1881].

Often gifts were received from Sir Walter about the same time. He gave John a little Shetland pony, which did not live long, and hearing this, a larger and much more serviceable one was presented to him. My father reciprocating the kindness by presenting to Charles Scott, his youngest son, a beautiful young horse of his own breeding and training. My elder half-brother, James Usher, having antiquarian tastes, presented to Sir Walter some valuable and much prized additions to his armoury, which were always graciously received and to which his name is still appended.

I well remember, on the consummation of the treaty with my father, Sir Walter dined in the old house at Toftfield, with Charles Erskine, the mutual friend and business man of both, and a few other friends. It so chanced that at the moment the gentlemen were descending from the drawing-room, Mary and I were going to bed and met them on the stairs. Sir Walter caught me in his arms and tried to kiss me. Like a little goose I struggled to get free and declined the honour, to my great regret in after life!

From the time of the purchase the name of the property was changed to Huntly Burn, this being the name of the little rivulet previously mentioned. As it came nearer the house it increased in volume, and was a very pretty feature as it passed through a wood of considerable size, which formed the extreme eastern boundary of the property. Just at its extremity was built a few years later a beautiful little cottage called Chief’s Wood, as the summer residence of Lockhart after he married Sir Walter’s eldest daughter. Here in after years he spent many happy days playing with his grandchild and cooling his champagne in the brook. Ten minutes walk from Huntly Burn led you through the wood to this sweet home of his daughter. I cannot help telling you of some happy memories I have of this sylvan scene for it was there my uncle Andrew used to delight in gumping trout when at Toftfield on a fishing excursion.[13] It was our great treat to accompany him, also my uncle Dunlop. They were great adepts and very successful in the sport, and it required their trousers and shirt sleeves should be well turned up. Sir Walter came very often to Huntly Burn after it was his own. His great hobby was planting, and the wide extent of moorland gave him ample scope for it, as he delighted to plan and superintend it himself. In the course of thirty years a dense forest of many acres formed a great improvement to that part of the estate.

It must have been nearly at the close of 1817 when our family left the place of their birthright — those not of age would feel it most, and to those who were of an age to realize all the sadness of it, it was no doubt a great trial. To myself and those I have named, leaving the nice new house was our great sorrow and yet we were pleased to go to a very pretty one in the immediate neighbourhood of Melrose.

Shortly after, the Fergusons took possession of their home at Huntly Burn, and Sir Walter of his far-famed mansion Abbotsford, which he had watched to its completion with so much interest, and where he was destined to enjoy the fullest tide of popularity awarded to literature in any age. His inspiration being then at its zenith, and the number and variety of his great works during the successive years unprecedented, and he became the hero of the world. His ‘worshippers’ came from all corners of it. He used to say “his house was like a cried Fair”, yet all were received with courtesy, many doubtless exclaiming like the Queen of Sheba of Solomon: “the half of his greatness was not told to us”. Even the humblest aspirants to literary fame who came for advice went away cheered and comforted by his large-hearted sympathy.

My good old grandmother Usher[14] used to say of Sir Walter: “What a pity so clever a man did not write sermons instead of novels”, but to those who were privileged to see him in the inner sanctuary of his home, his whole life was a sermon, and there he was beloved by all for his benevolence and his true goodness, far excelling his greatness. He assembled his household for prayers at a stated hour every morning — to which all visitors were invited — often having a large congregation. His servants worshipped him, and even the dumb animals showed a great love for him, down to the very pigs. His much-valued servant, forester, and factotum, Tom Purdie, was very faithful, but given to dram-drinking, and heedless of Sir Walter’s gentle rebukes. He was told on one occasion he must leave his service, but replied: “Deed, Sir, I’ll gang nae sic gait. If ye dinna ken when ye’ve gat a good servant, I ken when I’ve gat a gude maister.” On the occasion of another like offence, Sir Walter exclaimed: “Oh, Tam, Tam, I could trust you with untold gold, but not with unmeasured whiskey!”

In 1820 Sir Walter received the honour of a Baronetcy from George IVth with whom he was in great favour, and when in 1822 His Majesty paid a visit to Edinburgh, Sir Walter received him, and got the lion’s share of the great ovation he received while there.

Notwithstanding some threatening clouds on the horizon, his fame continued yet undimmed, and by redoubling his labours he thought to dispel them. The great wonder grew, by what magic was he able to do so? His time was being so fully engrossed with his professional work in Edinburgh, and his house when at Abbotsford filled with visitors to whom he devoted all his forenoons, driving them to Melrose Abbey, Rymer’s Glen, or to any other place of interest, or taking them to see all his improvements, when on some Rest and be Thankful he would keep them under the spell of his enchantment, while relating legends and anecdotes by the hour, his face beaming with enthusiasm. A charming description of his own experience on some such occasion as this is given by, I think, Washington Irving, during a visit of some days. Returning to lunch at Abbotsford, it was Sir Walter’s habit to retire on plea of taking some rest. On rejoining his friends the after part of the day was given entirely to their entertainment, no one seeming to be so little preoccupied as himself. The secret of his great powers in work lay in his making time. He was an early riser and shut up in one of the magic towers of his ‘castle’ where no sound could disturb him, he was at work sometimes for three hours before breakfast, then he had his two hours after lunch, and with the rapidity of both his pen and the flow of his ideas, a great amount was daily effected, though this was often interrupted by infirm health. His amanuensis and much esteemed friend, Willy Laidlaw, often found it difficult to keep up with the rapidity of his diction, and on one occasion requiring to wait for a second or two said, “Come, get on,” and was answered, “Oh, aye, it is very easy for you Willy, to say ‘get on’ but you forget I have every word to spin out of my brain.”

Sir Walter’s eldest daughter was in 1822 married to Lockhart, a son-in-law after his own heart. Walter in the following years sometimes came to see us. I remember once he was accompanied by Sir Adam Ferguson. He asked for the twins and we were brought from the schoolroom. On inspection, he said we were not so much alike as formerly and that he saw the difference. My father, seeing one of us wore a string of coral, said, “If I take them out of the room I bet you won’t know them.” He took us out, took off the necklet which as he guessed was the distinguishing mark, and Sir Walter was as much puzzled as usual. Only once again after a lapse of years when I was sixteen I met him in the stage-coach going to Galashiels. To my great mortification he did not know me. I was too shy to introduce myself though we were alone inside. I only mention this circumstance as an example his gracious manner even to a seeming stranger. He conversed pleasantly all the time, and I remember perfectly every word of the conversation. He was going to Edinburgh and when I left he expressed regret I was not going also.

Still in the meridian of his great power and honoured name, the years went on, his marvellous works so rapidly produced causing the wonder and admiration of the world. Yet, conscious and proud of his greatness, as he must have been, he never was vain and never talked shop, and was always ready to award merit to others of his craft. But alas for the mutability of all human prosperity. The clouds so long threatening burst at last with overwhelming calamity through the great failure of Constable, his London publisher, with whom Sir Walter in an evil hour had become a partner, and all was lost. Stunned, but not in despair with this unlooked-for blow, he set himself with wondrous courage to overcome it, and by superhuman efforts he so far succeeded in realising a sum I am afraid to name lest I exaggerate, yet think it was thirty thousand pounds, in about two years, but at what a sacrifice — the complete prostration of his great powers of both body and mind. This was the beginning of the end, and, too sad to think about, all that could be done for his restoration to health proved of no avail.

He was brought home from his melancholy journey to the Continent in a state of unconsciousness and taken to Abbotsford to die, and the saddest and last scene was enacted there, when he was carried into his study and placed in his own chair. A faint smile of intelligence and content lighted up his worn face as he recognised some members of his family, and the familiar objects around him, and he made signs for a pen, which was put into his hand but, alas, his fingers could not grasp it. He burst into tears and again became unconscious, and never rallied though he lived for some weeks surrounded by his family, and nursed by his loving daughter Miss Scott[15] who was his devoted companion through all his troubles and was so completely shattered in health she did not long survive him, nor did any of his family. His sons inherited nothing of his great qualities, only the name. All that survive at the present time to inherit the much-coveted estate is a great-granddaughter named Mrs Maxwell Scott[16] of whom I know nothing.

Unspeakably sad of such an honoured life to say, “It has passed away as a dream”, or “as a tale that is told” but all must yield to the immutable laws by which God governs the universe — the noblest as well as the most abject of his creatures. Yet the great and honoured name of Sir Walter Scott will live through many generations yet to come, while all his honours and ambitions have passed away.

[1]. The First Laird of Toftfield was John Usher, born 1710. Agnes’s twin sister was Mary Usher, forebear of the donor of this memoir. The Ushers are known to be Norman in origin and came over in the 11th century; the Usher genealogical table in my possession commences Melrose, 1626, and the most recent birth is dated 1956.

[2]. J. G. Lockhart, Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, first published 1837–38; the revised 2nd edition of 1839 is regarded as the standard edition.

[3]. Julie Lawson, “Ruskin on Scott’s Abbotsford” in Abbotsford and Sir Walter Scott: The Image and the Influence, ed. Iain G. Brown. Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 2003, pp. 161–68.

[4]. Raeburn, Sir Henry. Francis Nacnab. ca. 1810. National Portrait Gallery, London.

[5]. The First Laird of Toftfield was John Usher, born 1710. He purchased Toftfield in 1753. Agnes Cunningham exaggerates the duration of the patrimony; it endured for sixty-four years, not three hundred. However, it is possible that she is referring to other land holdings at Darnick, near Melrose, noted in the Melrose Parish Register.

[6]. The estate included the Rhymer’s Glen, which is associated with Thomas the Rhymer and the Queen of the Fairies, and in Scott’s day was planted with native broadleaf trees. In other words, an enchanted place.

[7]. Another exaggeration. This should read, five years (1815-1820).

[8]. Dr Adam Ferguson, Professor of Philosophy at University of Edinburgh.

[9]. The Ferguson sisters were: Isabella, the eldest, Mary, and Margaret. Walter Scott, The Journal of Sir Walter Scott, ed. W. E. K. Anderson. Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 1998. Internet. Inventory of Adam Ferguson CC20/7/8 p.574 (accessed 5 February 2019).

[10]. Wedder mutton: castrated male lamb, considered the most flavoursome.

[11]. Rummer, a large drinking-glass.

[12], John Usher (1809–1896) eldest of six sons of his father’s second marriage. John Usher, Poems and Songs. Kelso: Rutherford, 1894. In addition to his artistic accomplishments, John Usher was a noted sportsman and racing enthusiast in the district of Kelso.

[13]. To gump or guddle, (Scot.) to fish with the hands by groping under the stones or banks of a stream.

[14]. Margaret Usher, née Grieve, daughter of Hugh Grieve of Blainslee, nr. Melrose, Roxburghshire (1736–1825).

[15]. Anne Scott, 1803–1833.

[16]. Mary Monica Maxwell Scott née Hope Scott (1852–1920).